The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is charged with ensuring that a range of consumer products, like drugs, vaccines and medical devices, are safe and effective. However, most patients and consumers probably don’t realize that for the most part, the FDA is relying upon manufacturers to conduct their own tests and studies for later review by the agency. And then once the drug or device is out on the market, the FDA further relies upon manufacturers to conduct post-market review and report any issues back to the FDA, which could then initiate the need for an FDA Recall.

Sometimes the FDA and manufacturers will conclude that an approved drug or device is, in fact, not safe for use or consumption and needs to be removed from the market. The mechanism for doing so is called a “recall” and the level and depth of the FDA’s involvement in the recall depends a great deal on communication and cooperation with manufacturers who are sometimes reluctant to pull drugs and devices which are huge profit centers for them.

What Is Involved in an FDA Recall?

Typically, if a drug or device manufacturer or the FDA itself, decides that a device or drug is not safe and therefore should not be available to patients and consumers in the marketplace, a recall will be issued. More often than not, the reasons for a recall can range from:

- The drug or device causes dangerous side effects.

- Consumers have used the drug improperly causing serious injury or death;

- The FDA has discovered a safer alternative to the drug or device.

Different types of recalls can be issued based upon the relative danger of illness or harm posed by the drug or device:

| Type of Recall | Scope |

| Class I Recall | There is a reasonable probabilty that a consumer’s use of or exposure to a drug or device will cause serious health problems or death. |

| Class II Recall | Use of or exposure to a drug or device may cause temporary or medically reversible health problems, or there is a remote risk that the drug or device will cause serious health problems. |

| Class III Recall | Use of or exposure to a drug or device is not likely to cause adverse health consequences. |

| Market Withdrawal | The drug has a minor problem that the FDA would not normally monitor. For example, the manufacturer removes a drug from the market because of after-market tampering vs. a problem with the drug itself. |

| Medical Device Safety Alert | A medical device has an unreasonable risk of causing substantial harm. |

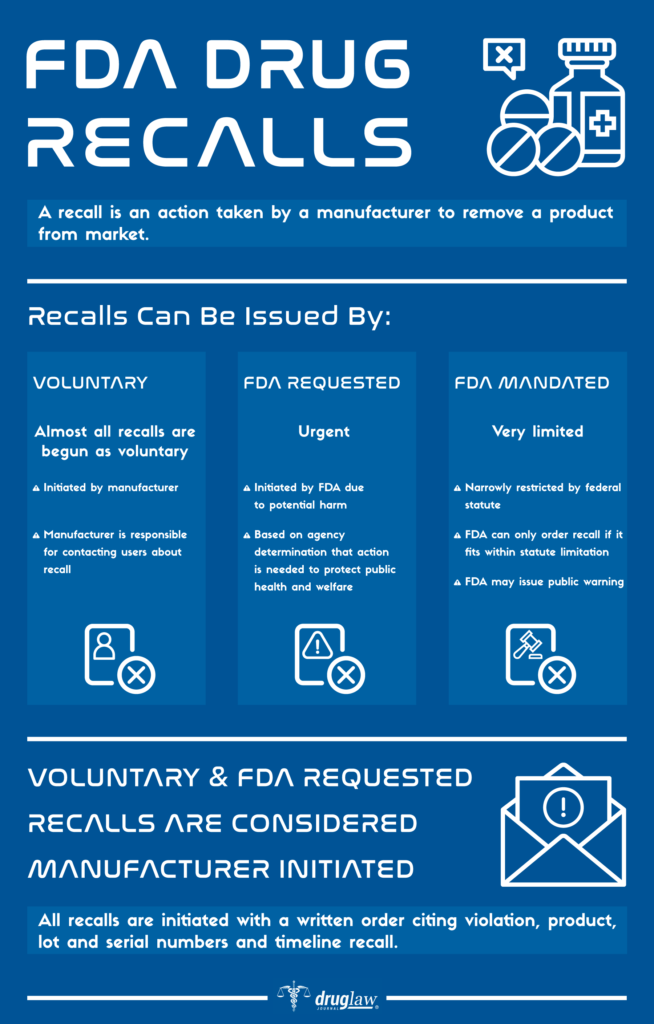

Who Issues a Recall?

There are three routes to triggering a recall:

1) The Manufacturer

It identifies the issue internally and then initiates the recall process. This is, in fact, the most common type of recall.

2) Voluntary Recall

The FDA informs a manufacturer that its product is defective and suggests or requests that the manufacturer recall the product.

3) Mandatory Recall

If a manufacturer refuses to recall a product, the FDA has regulatory authority to either seize a product or ask the courts to force the manufacturer to recall the product.

Once a manufacturer begins the drug recall process, it must notify the FDA and then follow-up with progress reports on the success of the recall. If the FDA issues a mandatory recall order, the manufacturer will usually comply. Rarely has the FDA used its powers to seize a drug or device.

How Will I Know if a Drug or Device Has Been Recalled?

The FDA and manufacturers have several routes with which to notify consumers and patients about product recalls. Most notably:

- Direct Notification: Manufacturers affirmatively telling the wholesalers, doctors and pharmacists in its retail supply chain about the recall and what to do with the product.

- Public Notification: The FDA reports on its Class I safety recalls routinely on its web site: “Recalls, Market Withdrawals and Safety Alerts”. Typically Class II and Class III recalls can be found in the FDA’s regularly published enforcement alerts.

- Media Notice: Popular and widely used drugs and devices which are recalled will usually attract a great deal of media attention.

What Are the More Noteworthy and Recent FDA Recalls?

| Product | Recall Date | Reason |

| Zantac (ranitidine) | 2020 | Concern over contamination by NDMA, a probable human carcinogen. |

| Bextra (valdecoxib) | 2005 | Concern over increased risk of heart attack and stroke in patients. |

| Eliquis (apixaban) | 2017 | Concern over a packaging error that mis-labeled the dosage. |

| Vioxx (rofecoxib) | 2005 | Concerns over increased risk of heart attack and stroke in patients. |

| DePuy Knee | 2010 | Concerns over high failure and replacement rate as well as functionality of the design. |

Sources Cited (14)

1) “What Is a Medical Device Recall?” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/medical-device-recalls/what-medical-device-recall

2) “Recalls, Corrections and Removals (Devices)” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/postmarket-requirements-devices/recalls-corrections-and-removals-devices

3) “Drug recall: An incubus for pharmaceutical companies and most serious drug recall of history” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4286830/

4) “The World’s Biggest Medical Device Recalls” https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/features/biggest-medical-device-recalls/

5) “FDA Regulatory Procedures Manual” https://www.fda.gov/media/71814/download

6) “Industry Guidance for Recalls” https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts/industry-guidance-recalls

7) “Characteristics of FDA drug recalls: A 30-month analysis.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26843501

8) “FDA 101: Product Recalls” https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/fda-101-product-recalls

9) “FDA Drug Recalls” https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/fda-drug-recalls-32997.html

10) “Study Reveals Most Common Reasons for FDA Recalls” https://www.empr.com/uncategorized/study-reveals-most-common-reasons-for-fda-recalls/

11) “Medical Device Recalls and the FDA Approval Process” Medical Device Recalls and the FDA Approval Process

12) “Critics Assail FDA Medical Device Approval Process” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3171816/

13) “Drugs and Devices: Comparison of European and U.S. Approval Processes” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2452302X16300638

14) “The FDA’s Authority to Recall Products” https://nationalaglawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/crs/RL34167.pdf

Black Box Warnings

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has primary responsibility for regulating what must be included on the labels, including Black Box warnings, for prescription pharmaceutical medications and biological products. What is included on the label derives primarily from disclosures to the FDA by drug manufacturers and are submitted as part of the approval process. Although the FDA drug approval process imposes many requirements on manufacturers in the drug “pre-approval” stage, these companies continue to have responsibility for monitoring the ongoing safety and efficacy of their products in “post-market”.

After approval, the FDA may require drug manufacturers to include additional new information on drug labels, such as boxed warnings which advise doctors and pharmacists that a particular drug may cause serious adverse reactions or other problems. These are known as “black box warnings” and are reserved for those drugs which have demonstrated a potential for side effects which can lead to death, disability or serious injury.

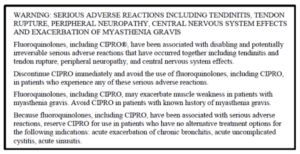

What Is the “Black Box” Warning?

The black box is the most substantial and serious of the on-label warnings that the FDA issues for drugs, while still allowing them to remain on the market. The name “black box” comes from the black-lined border around the text of the warning. Black box warnings must appear on the label of the prescription in order to alert physicians, pharmacists and consumers about safety concerns, serious side effects or risks to life. The information in a black box warning must provide a concise summary of the adverse effects and risks associated with the drug.

Here is an example of an FDA mandated black box warning on a label for Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics:

How Well Do Physicians and Pharmacists Understand the Warnings?

Although the black box advises consumers about serious side effects and risks, its primary purpose is to advise doctors and pharmacists as “learned intermediaries” and elevate the information to their attention. The FDA itself notes that black boxes are “…designed to make information in prescription drug labeling easier for healthcare practitioners to access, read and use to make prescribing decisions.”

Doctors are trained to be aware of the presence of black box warnings and as a general rule, always want their patients to have as much informed consent about their prescriptions as is possible. Many physicians have affirmed that black box warnings do affect their prescribing and treatment decisions – with some admitting to a hesitancy to prescribe anything with a black box warning unless no other treatment options or therapies are available.

Unfortunately, reports over the years suggest that the influence of black box warnings on physicians is not uniform owing to either a lack of understanding about the meaning of the black box or just simply being unaware of the warning itself. In a Harvard Medical School study of 930,000 ambulatory care patients, it was learned that 42% of patients had received prescriptions for black box labeled medications and that corresponding physician compliance with the recommendations on the label were “variable” in nature.

Furthermore, non-profit foundations and agencies which monitor the FDA have expressed concerns about the effectiveness of black box warnings. The sheer volume of post-market warnings issued by the FDA is leading some physicians to complain of “data fatigue” as the cause for overlooking drug warnings. For example: in 2004, the FDA issued 68 safety alerts for market recalls for drugs and devices. In 2005, that number shot up to 127. Accordingly, some experts have even gone so far as to claim that the FDA is losing its ability to influence the practice of medicine and prescribing of drugs, brandishing estimates that as many as 80% of safety warnings are overlooked by physicians and pharmacists.

The FDA “Fast Track” Process

If physicians and pharmacists are overwhelmed by warning data coming from the FDA, is it possible that too many dangerous drugs are making it through the approval process without further study? Some experts think so.

In 1988, the FDA introduced its first “fast track” drug approval process to facilitate the “development and expedite the review of drugs to treat serious illnesses and fill unmet medical need”. In essence, fast track was created to shorten the approval process for serious or rare diseases, especially those without other available treatments. However, in 1992 fast track was augmented by the FDA with two additional avenues for approval: “priority review” and “accelerated approval”.

Since 1992 and the enactment of these additional expedited aveues, median approval times for new drugs decreased from 33.6 months to 16.1 months. Accordingly, some experts and their counterparts in the drug manufacturing industry point to this fact and argue that the fast track process provides benefits for society-at-large with more medications getting onto the market in shorter time. However, others argue that it has also undermined safety fundamentally. They note that between 1999 and 2009, outpatient prescribers in the United States wrote more than 30 million prescriptions for each of nine drugs (for a total of 270 million prescriptions) that were subsequently removed from the market for safety reasons or which received black box warnings for potentially lethal side effects.

One statistical study, researched over several years and presented for review in 2014, concluded that newly approved drugs have a one-in-three chance of acquiring a new black box warning or being withdrawn for safety reasons within 25 years of FDA approval. This study made the recommendation that the FDA: a) strengthen drug approval standards (i.e. increase approval times); and b) that physicians should rely on drugs with longer market exposure and established track records – unless it involves a truly breakthrough therapy.

Future of Black Box Warnings

For too many physicians, the black box warnings are opaque in their meaning and lack the reasoning that seasoned medical professionals utilize when evaluating the needs of their patients. Furthermore, the FDA relies upon a system of post market “surveillance” for learning about adverse effects, that is itself wholly reliant upon the drug manufacturer collecting and reporting adverse data to the FDA. For these reasons, many both in the consumer safety and drug regulatory fields feel that the FDA should: a) improve and strengthen the methods it uses to communicate adverse side effects to physicians and pharmacists; b) increase scrutiny and approval times for drugs in the pipeline; and c) enhance post-market surveillance with less reliance on reporting by the manufacturers themselves.

Sources Cited (14)

1) “A Guide to Drug Safety Terms at FDA” https://www.fda.gov/media/74382/download

2) “What Does it Mean if My Medication Has a ‘Black Box’ Warning?” https://health.clevelandclinic.org/what-does-it-mean-if-my-medication-has-a-black-box-warning/

3) “New and Incremental FDA Black Box Warnings From 2008 to 2015” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29215916/

4) “Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Formulary Restrictions After Postmarket FDA Black Box Warnings” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31663461/

5) “The meaning behind black box and other drug warnings” https://www.healio.com/pediatrics/practice-management/news/print/infectious-diseases-in-children/%7B2f3d205a-694f-4ff0-9d60-56563e17f149%7D/the-meaning-behind-black-box-and-other-drug-warnings

6) “Black box” 101: How the Food and Drug Administration evaluates, communicates, and manages drug benefit/risk” https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(05)02325-0/fulltext

7) “Expedited drug review process: Fast, but flawed” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4936080/

8) “Era Of Faster FDA Drug Approval Has Also Seen Increased Black-Box Warnings And Market Withdrawals” https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0122

9) “Why You Should Pay Attention to Black Box Warnings on Medication” https://www.verywellhealth.com/black-box-warnings-1124107#what-does-one-look-like

10) “Physicians May Overlook Black Box Warnings” https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/pn.41.6.0013

11) “Consumers Tune Out FDA Warnings” https://money.cnn.com/2008/02/22/news/companies/fdawarning_fatigue/index.htm

12) “The consent risks with ‘black box’ warning medication” https://www.hrmronline.com/article/the-consent-risks-with-black-box-warning-medication

13) “What is a Black Box Warning for a Drug?” https://www.everydayhealth.com/fda/what-black-box-warning-drug/

14) “Doctors often ignore ‘black box’ warnings on drugs” https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/120625-doctors-often-ignore-black-box-warnings-on-drugs

510(k) Device Clearance

According to the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA), all medical device manufacturers must register their facilities and list their devices with the Food and Drug Administration. In the U.S., these devices must generally follow one of two paths to market, either: the Pre-Market Approval (PMA) application process; or the 510(k) Device Clearance “notification” which allows device manufacturers to bypass the more rigorous PMA process entirely. The FFDCA does not require that every medical device on the market in the U.S. be subjected to FDA review. However, those devices which present moderate-to-high risk issues for the health and safety of patients and consumers must be subjected to a review process prior to entry in the market.

Bearing this divergence in mind, the FDA set a new record for device approvals across the board in 2018, with most coming through the 510(k) clearance process. Furthermore, between 1996 and 2009, the FDA approved 48,402 applications through 510(k) clearance and generally speaking, roughly 85% of these applications are cleared annually on the basis that the applicant is “substantially equivalent to an earlier, approved device.

In the meantime, between 2005 and 2009, there were 113 device recalls on the basis of issues that the FDA determined could cause serious health problems or death. Over 71% of these devices were cleared through the 510(k) process. This surge in recalls has prompted many advocates for patient safety to question a system which they feel is allowing too many dangerous devices through which cause harm or worse to the patients they are supposed to help.

Overview of the 510(k) Clearance Process

The FDA regulates virtually every medical device on the market in the U.S. today. The amount and depth of scrutiny, regulatory controls and in some instances, restrictions on marketability, are all tied to the FDA’s medical device classification system. Those device classes are:

| Classification | Threshhold | Examples |

| Class I | General controls are sufficient to provide reasonable asurance of the safety and effectiveness of the device. The device has a low risk of illness or injury to patients. | Elastic bandages, examination gloves, handheld surgical instruments. |

| Class II | General controls are insufficient to provide reasonable asurance of safety and effectiveness of the device. These devices pose a moderate risk to patients. | Powered wheelchairs, infusion pumps, surgical drapes. |

| Class III | Cannot be classified as either Class I or Class II because there is insufficient information that special controls would provide reasonable assurance of the device’s safety and effectiveness. These devices are generally purported to be for use in supporting or sustaining human life or for a use which is of substantial importance in preventing impairment of human health. | Heart valves, silicone gel-filled breast implants, implanted cerebella stimulators; metal-on-metal hip joints and certain dental implants. |

Medical devices which fall under Class II and Class III which are not “substantially equivalent” to an already approved medical device must route through the FDA’s rigorous PMA process. That means the device manufacturer will have to submit clinical data to support claims about the safety and effectiveness of the device.

Devices which can claim substantial equivalence to an already approved device may divert through the abbreviated 510(k) process as an alternative to PMA. Instead of demanding evidence for approval, as with the PMA process, the FDA instead “clears” a device for the market as long as the manfucatrer can demonstrate its equivalence to an already approved device. In other words, within 510(k), the FDA is not actually examining any device to determine if the manufacturer’s claims about its safety or effectiveness are actually true. Note: about 80% of all medical devices submitted to the FDA are routed through 510(k) clearance.

510(k) Clearance and Potential Dangers from Lack of Oversight

Medical journals and public interest research groups for years have noted that “fast-tracking” devices to the market, such as through the 510(k) clearance process potentially correlates to a spike in device recalls. One of the most prominent product recalls for a device claiming substantial equivalency involved a common device implanted in thousands of patients. In 2005, the DePuy Orthopaedics division of Johnson and Johnson marketed a new metal-on-metal replacement hip-joint design. The new joint design was cleared through the 510(k) clearance proces and was implanted in over 100,000 people. However, after receiving a barrage of complaints of pain and illness stemming from erosion of the metallic parts, the DePuy hip was recalled in 2010.

Additionally, in 2018, as part of a long-running collaborative investigation between the AP, NBC and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, it was learned that across all types of medical devices, more than 1.7 million injuries and 83,000 deaths were reported to the FDA over the previous decade. Between 2008 and 2017, it was found that nearly one quarter of all device injury reports came only from a few devices which went through the truncated approval process:

- Surgical Mesh – 60,795 injuries

- Hip Prosthesis – 103,104 injuries

- Spinal Stimulator – 78,172

- Defibrilator – 59,457

- Insulin Pump Implant – 60,561

- Insulin Pump with Sensor – 94,826

Despite these issues, the FDA does not believe that its role as a regulator has been compromised or rendered less effective than perhaps is believed. Although the agency has expressed some reservations about the limitations of the data it collects and its ability to assess death or injury due to the use of any medical device, it does not believe its oversight role is failing. At a recent industry conference, Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, the Director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, stated that “There are over 190,000 different devices on the U.S. market. [The FDA] approves or clears about a dozen new or modified devices every single business day… The few devices that get any attention at any time in the press is fewer than the devices we may put on the market in a single business day. That to me doesn’t say that the system is failing. It’s remarkable that the system is working as it does.” He went on to say “Unfortunately, the FDA cannot always know the full extent of the benefits and risks of a device before it reaches the market…”

The Future of the 510(k) Process

In 2018, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a 245-page report evaluating the previous 35 years of the 510(k) process. The report contained broad recommendations and findings, among them that pre-market clearance based on “substantial equivalence” does not generally make for adequate ability to ascertain the safety and effectiveness of medical devices. The report further suggested that the FDA would do better to directed at development of a new pre-market clearance framework combined with more “post-market surveillance” of devices alleged to be harming patients.

Despite these recommendations, Dr. Shuren and the FDA have continued to “build out” the 510(k) program, organizing a new Office of Product Evaluation and Quality in 2019 and issuance of its “Safety and Performance Based Pathway, Special 510(k) Program”. Even so, experts who have followed the FDA’s approach to 510(k) over the years remain skeptical of the agency’s reorganization proposals which they feel are short of the substantial oversight changes they feel are necessary.

Sources Cited (18)

1) “510(k) Submission Process” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-notification-510k/510k-submission-process

2) “FDA Regulation of Medical Devices” https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42130.pdf

3) “IOM, Public Health Effectiveness of the FDA 510(k) Clearance Process: Measuring Postmarket Performance and

Other Select Topics” https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13020/public-health-effectiveness-of-the-fda-510k-clearance-process-measuring

4) “Medical Devices: FDA should take steps to ensure that high-risk device

types are approved through the most stringent premarket review process” https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-09-190

5) “510(k) Clearances” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/device-approvals-denials-and-clearances/510k-clearances

6) “How Long Does the FDA 510(k) Review Process Really Take?” https://www.meddeviceonline.com/doc/how-long-does-the-fda-k-review-process-really-take-0001

7) “A History of Medical Device Regulation & Oversight in the United States” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/overview-device-regulation/history-medical-device-regulation-oversight-united-states

8) “U.S. Medical Device Clearance: Navigating the FDA 510(k) Premarket Approval Proces for Medical Devices” https://legacy-uploads.ul.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/2015/02/UL_WP_Final_U.S.-Medical-Device-Clearance-Navigating-the-FDA-Premarket-Approval-Process-for-Medical-Devices_v5_HR.pdf

9) “510(k) Premarket Notification Analysis of FDA Recall Data” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209655/

10) “Medical Devices and the Public’s Health” https://www.nap.edu/read/13150/chapter/1#vii

11) “Key Differences Between 510(k) and PMA Pathways at the FDA” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=05kw8zA27Cg

12) “FDA sets novel device approval record for 2018, outlines new criteria for 510(k) clearances” https://www.fiercebiotech.com/medtech/fda-sets-novel-device-approval-record-for-2018-outlines-new-criteria-for-510-k-clearances

13) “Medical Device Recalls and the FDA Process” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21321283

14) “FDA to overhaul more than 40-year-old process for approving medical devices that some say puts consumers at risk” https://www.cnbc.com/2018/11/26/fda-to-overhaul-510k-medical-device-approval-process.html

15) “Spinal Cord Stimulators Help Some Patients, Injure Others” https://apnews.com/86ba45b0a4ad443fad1214622d13e6cb

16) “Medical Implant Recalls Raises Questions About 510(k) Review Process” https://uspirg.org/blogs/blog/usp/medical-implant-recalls-raises-questions-about-510k-review-process

17) “Institute of Medicine Report Medical Devices and the Public’s Health: The FDA 510(k) Clearance Process at 35 Years” https://www.policymed.com/2011/07/institute-of-medicine-report-medical-devices-and-the-publics-health-the-fda-510k-clearance-process-a.html

18) “Regulatory Development of the Year: 510(k) changes inch along” https://www.medtechdive.com/news/regulation-fda-medical-device-510k-dive-awards/566238/

Pre-Market Approval Process

Pre-Market Approval (PMA) is the name of the process the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) utilizes to review and evaluate the safety and effectiveness of medical devices which present a risk so great that ordinary regulatory controls are insufficient to guarantee their safety and effectiveness. PMA is the most stringent control the FDA has on medical device marketing, requiring applicants to supply copious amounts of valid scientific evidence prior to receiving approval from the agency.

Which Devices Are Required to Undergo PMA?

Medical devices are regulated by the FDA and can encompass a broad range of objects ranging from tongue depressors, to stethoscopes, lab equipment, surgical instruments and life supporting equiment such as ventilators. The FDA subjects “Class III” medical devices to PMA review. These are medical devices that support or sustain human life, or are substantially important for preventing impairment of human health, or themselves present a potential, unreasonable risk of illness of injury.

Agency approval of a PMA for a Class III device requires that the applicant establish a “reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness” with scientific evidence. What this means is that the FDA will be looking for whether the device’s probable benefits outweigh its probable risks; while examining results of studies for effectiveness. The evidence the FDA examines during the PMA process typically includes:

- Studies and Trials

- Case Histories

- Reports of Significant Human Experience

History of Premarket Approval

The FDA began regulating medical devices following the enactment of the 1976 Medical Device Amendments to the federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Prior to that point, medical devices were not required to undergo any sort or federal oversight and inspection. Instead, they were regulated by a patchwork of state consumer protection laws applicable to all different types of consumer products.

The Medical Device Amendments created three classes of medical devices based upon their risk to patients. Class I devices are considered “low risk” (i.e. bandages and stethoscopes), Class II are “medium risk” (i.e. blood pressure cuffs, peripheral vascular catheters); and Class III “high risk”. Class I devices are generally exempt from FDA review, requiring only registration and adherence to basic FDA standards and practices. Class II devices can usually bypass the PMA process if they are deemed “substantially equivalent” to a preexisting device cleared for marketing. This process is known as the 510k pathway and does not require the rigorous testing that PMA demands. Generally speaking, all Class III devices are required to be reviewed under the PMA process, although a select few have been permitted to bypass PMA through the 510k process, something which has attracted substantial criticism in recent years.

How Does the PMA Process Work?

PMA review is a complex process that extends over multiple layers of review once the application process commences. First, the device manufacturer or patent holder must submit an application for PMA to the FDA. The agency will then conduct a “limited scientific review” of the application to determine if it is suitable for filing. Once the FDA is satisfied with the application package, it will clear the device for more thorough and in-depth review. Next the FDA will begin a thorough investigation of scientific and clinical data submitted by the applicant, as well as examine quality systems and regulatory compliance. Following this intense review stage, the FDA may subject its findings to an outside panel of experts called an “Advisory Committee”, which will hold public meetings and submit a final report to the FDA. Finally, the FDA will convene for final deliberations, documentations and then notify the applicant of its decision. The timeframe from start-to-finish for PMA review is typically anywhere between 240-350 days.

User Fees

A substantial component to the PMA process involves the user fees charged to manufacturers. The FDA collects user fees for the review of original PMAs and supplements. In recent years, the cost of an original device application was in excess of $250,000. These amounts are adjusted approximately every 5 years by Congress.

What Happens After a Device is Approved Through the PMA Process?

Once a device receives approval through PMA, manufacturers may make incremental changes to a device design without re-submitting it again. These changes are regarded as part of the normal “product life cycle” and the deference accorded to devices in this respect is very different from the process for drug approval where any change to the active ingredient would require a completely new FDA authorization.

When a device manufacturer decides to make changes or “supplement” an approved design, they can do so through varied review processes. The most substantive changes to a device design undergo a “panel track” supplement review where an independent panel of experts oversees the process and reviews newly collected scientific and clinical data to support the supplemental application. Other major changes, such as an improved design element may be approved within a 180-day window supported by limited “pre-clinical” data. Minor changes to correct any post-approval issues, such as battery life, may be handled by a “real-time” review conducted by the FDA without any need for additional clinical data.

Any change which does not alter the device itself, such as a change to a manufacturing process, only requires notice to the FDA. Changes to the device’s label to address newly discovered safety concerns can be made through a “special supplement” process wherein the manufacturer can make the change prior to formal approval by the FDA.

What Are the Legal Implications of the PMA Process?

When Congress handed oversight of medical devices to the FDA, it included language in the legislation which “preempts” legal claims against approved device manufacturers under state law (where most product liability claims arise). This application of the preemption doctrine was further refined in 2008 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Riegel v. Medtronic that the PMA process specificially exempts approved manufacturers from state product liability tort claims.

It is worth noting however, that in the 1996 case Medtronc v. Lohr the Supreme Court did not extend the same preemption shielding to manufacturers who had bypassed the rigors of PMA, instead electing to seek approval under the 510k route. The court then reasoned that the “substantial equivalence” standard enumerated by the 510k process did not justify preeemption. Accordingly, only “high-risk” devices that run the PMA gauntlet are shielded from product liability claims.

Sources Cited (15)

“Premarket Approval (PMA)” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-submissions/premarket-approval-pma

2) “PMA Review Process” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-approval-pma/pma-review-process

3) “FDA’s Role in Regulating Medical Devices” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/home-use-devices/fdas-role-regulating-medical-devices

4) “An Overview of FDA Regulations for Medical Devices” https://www.einfochips.com/blog/an-overview-of-fda-regulations-for-medical-devices/

5) “Drugs, Devices, and the FDA: Part 2: An Overview of Approval Processes: FDA Approval of Medical Devices” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2452302X16300183

6) “FDA Authorization of Medical Devices” https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1817798

7) “U.S. Medical Device Clearance: Navigating the FDA 510k Premarket Approval Process for Medical Devices” https://legacy-uploads.ul.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/2015/02/UL_WP_Final_U.S.-Medical-Device-Clearance-Navigating-the-FDA-Premarket-Approval-Process-for-Medical-Devices_v5_HR.pdf

8) “FDA approval of cardiac implantable electronic devices via original and supplement premarket approval pathways, 1979-2012.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24449317

9) “How do Orthopaedic Devices Change After Their Initial FDA Premarket Approval?” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4773325/

10) “PMA Historical Background” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-approval-pma/pma-historical-background

11) “Approval of High-Risk Medical Devices in the US: Implications for Clinical Cardiology” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4080312/

12) “FDA Regulation of Dental Devices: Past, Present, and Future” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227820169_FDA_Regulation_of_Dental_Devices_Past_Present_and_Future

13) “The 510(k) ancestry of a metal-on-metal hip implant.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23301729

14) “User fees and beyond–the FDA Safety and Innovation Act of 2012” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23034017

15) “Life after Riegel: a fresh look at medical device preemption one year after Riegel v. Medtronic, Inc.” https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/foodlj64&div=19&id=&page=

Bayer Roundup Claims

Bayer will be paying $10.5 billion to settle U.S. claims that Roundup, its weedkiller, has lead to cancer in nearly 100,000 patients.

Bayer will be paying $10.5 billion to settle U.S. claims that Roundup, its weedkiller, has lead to cancer in nearly 100,000 patients.

Bayer AG introduced on Wednesday it struck an about $10.5 billion deal to work out countless claims with U.S. complainants affirming the firm’s Roundup herbicide causes cancer. Wednesday’s deal complies with months of talks between Bayer and also plaintiffs’ lawyers.

Bayer, which additionally makes pharmaceuticals, inherited countless legal actions against Roundup’s developer Monsanto Co. when it acquired the U.S. farming titan in 2018. Bayer has actually argued that Roundup is safe and also has repetitively protected the Monsanto bargain.

As part of the case, Bayer will pay some $9.5 billion to settle claims brought by attorneys standing for some 95,000 plaintiffs. It will set aside an added roughly $1.1 billion to establish and fund a panel to examine whether the item causes cancer cells to support future cases.

Bayer to pay $10.5B to settle 100,000 Roundup cancer claims in US

Politico

Bayer has agreed to pay about $10.5 billion to settle claims in the U.S. that its weedkiller Roundup led to cancer in nearly 100,000 patients exposed to the popular herbicide, according to a law firm representing some of the plaintiffs.

Read More >>

Bayer to Pay Up to $10.9 Billion to Settle Lawsuits Over Roundup Weedkiller

Wall Street Journal

Bayer AG said Wednesday it would pay up to $10.9 billion to settle tens of thousands of lawsuits with U.S. plaintiffs alleging the company’s Roundup herbicide causes cancer, a milestone in the German company’s legal battle that has been weighing down its share price for nearly two years.

Read More >>

Roundup Maker to Pay $10 Billion to Settle Cancer Suits

The New York Times

Bayer faced tens of thousands of claims linking the weedkiller to cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Some of the money is set aside for future cases.

Read More >>

Bayer agrees to pay $10 billion to settle Roundup weedkiller cancer claims

Axios

Bayer has agreed to pay just over $10 billion in order to settle roughly 125,000 claims that its Roundup weedkiller cases cancer and resolve potential future litigation, the company announced on Wednesday.

Read More >>

Bayer reaches $10.5 billion Roundup settlement

Market Watch

Bayer AG is set to announce on Wednesday it struck a roughly $10.5 billion deal to settle tens of thousands of lawsuits with U.S. plaintiffs alleging the company’s Roundup herbicide causes cancer, a milestone in the German company’s legal battle that has been weighing down its share price for nearly two years, according to a person familiar with the deal.

Read More >>

Have you or a loved one been impacted by Roundup?

Contact us below to learn about your options.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration Approval Process

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is one of the nation’s oldest regulatory agencies and, among its responsibilities, it is charged with ensuring the safety and effectiveness of drugs and medical devices in the U.S. market. The FDA itself is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and its leader is the Commissioner of Food and Drugs (also known as the “FDA Commissioner”).

The FDA separates its regulatory responsibilities into two broader frameworks. First, the FDA will review data and studies to determine the safety and effectiveness of a submitted drug or device application prior to its entry into the market – also known as the “premarket approval” stage. Once a drug or device has passed the premarket threshold and is approved, the FDA continues to monitor each applicant through “postmarket” data submissions and performance studies.

Even though the FDA’s mission as well as the premarket and postmarket processes seem pretty straightforward, they are, in fact, riddled with regulatory, scientific and legal standards that give some wiggle room to both applicants and the FDA itself when determining whether a drug is safe and effective or whether a drug or device can bypass entire stages in the review process. For some approved drugs and devices, key safety concerns with life-altering consequences may only materialize or are discovered after these products have been on the market for years. Between 1993 and 2010, seventeen drugs were approved by the FDA and then later withdrawn. It is estimated that during this time, these drugs were prescribed over 112 million times. Nine of these drugs were prescribed more than 1 million times prior to market withdrawal.

Accordingly, in an age when commercials for over-the-counter and prescription drugs are everywhere on television, radio and the interest; and where family doctors are routinely pressured by manufacturers to prescribe their specific medications and devices; it is more important than ever for consumers to arm themselves with information about the possible side effects, potential for injury and other issues involved with FDA approved drugs and devices.

Overview of the FDA Drug Approval Process

All prescription drugs marketed within the United States must have approval from the FDA. In order to receive that approval, drug manufacturers must first demonstrate the safety and effectiveness in accordance with the laws and regulations administered by the FDA. Additionally, manufacturers are required to ensure that their manufacturing facilities pass FDA inspection and that all drug labeling is approved by the FDA.

Something most Americans probably don’t realize is that the development of the prescription medications they are prescribed on a daily basis often begins long before the FDA’s involvement. In fact, most research and development on new prescription drugs takes place in university, hospital and government laboratories, oftentimes funded entirely by the federal government itself. If this research yields a formula that looks promising, government and private research groups will then develop a prototype. If the prototype looks like it will be profitable drug idea or component, then private industry will pick it up and develop it further in anticipation of submission to the FDA for approval.

Investigational New Drug Application

Except under very limited circumstances, the FDA will require safety and effectiveness data from clinical trials. These trials are designed, conducted and analyzed in accordance with FDA standards and involve studies of human subjects. Prior to clinical trials, the drug manufacturer will file an Investigational New Drug (IND) application with the FDA. This application must include, among other things: data from animal trials; a description of what the drug does; and its intended use. The FDA will then review this application and within 30 days either object or approve the start of clinical testing.

Clinical Trials

Once the FDA authorizes IND status to a new drug, the manufacturer sponsor will assemble research on a smal number of human volunteers. “Phase I Clinical Trials” will attempt to ascertain:

- Dosage

- How a drug is metabolized and excreted

- Any acute side effects

After the manufacturer sponsor evaluates the results of Phase I, it will then decide whether to proceed to “Phase II and Phase III” trials to gather evidence of a drug’s effectiveness in a larger group of test subjects that possess the qualities or characteristics that the drug is designed to address.

New Drug Application

Following the completion of clinical trials, the manufacturer sponsor will submit a New Drug Application (NDA) to the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). The NDA will include previously submitted data about manufacturing assurances as well as:

A detailed product description

- Product indications (the diseases or conditions it treats)

- A proposed label

- A proposed Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).

Throughout the NDA review, the CDER will evaluate drug safety and effectiveness data, label accuracy, samples and inspect facilities where the finished product will be made.

Review of the NDA

While reviewing the NDA, the FDA will consider three larger questions:

- Is this drug safe and effective for its proposed use? Do the benefits of this drug outweigh its risks?

- Is the drug label appropriate and does it contain the proper information?

- Has the manufacturer instituted sufficient controls to maintain and ensure the drug’s quality, strength and purity?

In particular, FDA scientific and regulatory staff will prepare several assessments covering a wide range of medical, clinical and risk mitigation topics relevant to the applicant drug. The law requires that the FDA approve only after it has received “substantial evidence” of a drug’s safety and effectiveness. However, the FDA has flexibility in determining what it requires as evidence. It can rely on studies solely from those of the manufacturer itself or at its discretion include independent studies and evaluations in its review. Sometimes, the FDA will even convene an advisory panel of outside experts to review data, although the FDA is not bound by their recommendations. Once the FDA makes a final determination, the agency will send out either an approval letter or a “complete response letter” detailing where the NDA fell short of approval.

Generic Drugs and the Approval Process

In 1984, Congress passed the “Hatch-Waxman Act” which established an abbreviated pathway for so-called “generic” drugs. Specifically, it allows manufacturer sponsors to submit an “Abbreviated New Drug Application” or ANDA (as opposed to a full NDA). The ANDA allows the manufacturer to bypass the replication and submission of animal and clinical trial data – instead relying on the data submitted by the manufacturer sponsor from the original NDA. The ANDA must only demonstrate that the generic equivalent is pharmaceutically the same as the original “brand name” product submitted under the NDA.

Special Regulatory “Fast Tracking”

Drugs that address “unmet needs” or “serious conditions” or address other criteria associated with “improved public health”, the FDA uses several formal mechanisms to expedite the drug development and review process. Specifically:

- Fast Track and Breakthrough Products: Fast tracking does not necessarily mean a reduction in the data submitted by the manufacturer, as much as it compresses the time the agency takes to convene experts and meet to decide a drug’s NDA.

- Accelerated Approval/Animal Efficacy Approval: If a drug is deemed necessary, but human trials are not ethical or feasible, approval of a drug may be based on animal control studies alone.

- Priority Review: Again, this does not impact the data which must be submitted, but compresses the timeline for review by the FDA itself.

Over-the-Counter Drug Approval

Over-the-Counter (OTC) drugs are sold directly to consumers without a prescription. Like prescription medications, OTCs are regulationed by the FDA and treat many common ailments such as pain, fever, cough/cold and upset stomach. Because OTC drugs are taken outside of the supervision of a physician, they generally require a wider margin of safety for their routine use and labeling that ordinary consumers can understand. OTC drugs may be manufactured and sold without going through a standard NDA process. An OTC drug must only “conform” to an OTC monograph – a regulatory standard for the labeling of ingredients within the product.

Overview of the FDA Medical Device Approval Process

As with drugs, many medical devices must be reviewed bny the FDA prior to their being legally marketable in the United States. However, not all devices receive the same level of review and as American patients are finding out, lack of review and scrutiny can result in painful consequences and a lifetime of suffering.

The FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) bears primary responsibility for medical device review. Under U.S. law, all medical device manufacturers must register their manufacturing facilities and list their devices with the FDA. The FDA will then classify those devices on the basis of the risk they pose to patients: low; moderate or high. Moderate or high-risk devices must seek “pre-market approval” from the FDA with an application that assures the FDA of the device’s safety and effectiveness.

Standard Pre-Market Approval

The ordinary Pre-Market Approval (PMA) process is tightly controlled by the FDA. A PMA application is based upon the FDA’s determination that the manufacturer’s application contains sufficient valid scientific evidence to provide a “reasonable assurance” that the device is safe and effective for its intended use. Approval of a PMA requires that the FDA review copious clinical and scientific data about the device and how it will perform in human subjects. Additionally, the FDA may convene advisory panels to review and make recommendations based upon the submitted data. The approval timeframe for a full PMA can take months or years. In 2015, 98% of PMAs accepted for filing were approved by the FDA.

510(K) Notification

In contrast to the rigorous evaluation and application protocols within the PMA application process, the FDA will also allow some manufacturers of “moderate risk” devices to bypass the PMA altogether and fastlane products onto the market with comparatively little scrutiny. Using what is termed as the “510(k) Notification” or “510(k) Approval” pathway, manufacturers can submit new products which can trace their lineage back to a pre-approved product with only “minor” technical, design or performance changes – also known as “substantial equivalence”. Many 510(k) applicants trace their “substantial equivalence” lineage back to products which were approved by various state regulatory agencies before the FDA was given regulatory authority in the 1970s.

Between 1996 and 2009, more than 80% of the devices cleared by the FDA posed a “moderate risk” (Class II) and the General Accounting Office (GAO) found that 25% of the Class II devices implanted between 2003 and 2007 were either “implantable, life sustaining or presented a significant risk to the health safety and welfare of the patient”. It is worth noting that the FDA cleared 90% of 510(k) submissions reviewed during this same time period.

In 2008, an orthopaedic device made by ReGen, a New Jersey company, was cleared for market using the 510(k) process. In April 2009, the then-Acting FDA Commissioner initiated an internal review of the decision to clear the ReGen MenaFlex device. The FDA report that ensued provided a list of 22 instances wherein the FDA did not follow established processes, procedures or practices. The final report chalked up many of the issues at the FDA to broad “confusion” about the legal standards imposed by the 510(k) process.

Criticism of the 510(k) Process

At the behest of the FDA, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) studied the 510(k) process and produced a significant report with many suggestions and criticisms of the process. Overall, the IOM recommended that the 510(k) process be “replaced with an integrated premarket and postmarket regulatory framework that effectively provides a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness throughout the device life cycle”.

It is worth noting that the 510(k) process has not been duplicated elsewhere (in contrast to the FDA’s drug application system – which has been replicated in many other countries). Other countries continue to tightly regulate medical devices and do not rely on “substantial equivalence” to a previously approved device for market clearance.

Sources Cited (13)

1) “Development & Approval Process | Drugs” https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs

2) “The Drug Development and Approval Process” https://www.fdareview.org/issues/the-drug-development-and-approval-process/

3) “How are drugs approved for use in the United States?” https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/pharma/conditioninfo/approval

4) “How the FDA Approves Drugs and Regulates Their Safety and Effectiveness” https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R41983.pdf

5) “The FDA’s New Drug Approval Process: Development & Premarket Applications” https://drug-dev.com/fda-update-the-fdas-new-drug-approval-process-development-premarket-applications/

6) “NIH and FDA Announce Collaborative Initiative to Fast-track Innovations to the Public” https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-fda-announce-collaborative-initiative-fast-track-innovations-public

7) “A step-by-step breakdown of the FDA’s drug approval process” https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/supply-chain/a-step-by-step-breakdown-of-the-fda-s-drug-approval-process.html

8) “From Idea to Market: The Drug Approval Process” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11572541/

9) “The FDA approval process for medical devices: an inherently flawed system or a valuable pathway for innovation?” https://jnis.bmj.com/content/5/4/269

10) “FDA Regualtion of Medical Devices” https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42130.pdf

11) “Over 100 million prescriptions written before drug safety recalls” https://pnhp.org/news/over-100-million-prescriptions-written-before-drug-safety-recalls/

12) “FAQs About the Regulation of OTC Medicines” https://www.chpa.org/FAQsRegOTCs.aspx

13) “Facts About Generic Drugs” https://www.fda.gov/media/83670/download#:~:text=FDA%20requires%20generic%20drugs%20to,as%20the%20brand%2Dname%20drug.&text=Many%20generic%20drugs%20are%20made,as%20the%20brand%2Dname%20drugs.

Eli Lilly and Company

Executive Summary

Eli Lilly and Company, Inc. (Lilly) is a global pharmaceutical manufacturer founded in 1876 by the company’s eponymous founder, Eli Lilly, an Indiana cotton farmer turned pharmacy entrepreneur. Today, Lilly is a Fortune 500 company netting over $20 billion dollars a year from pharmaceutical and over-the-counter drug sales. Through its global research and supply network, Lilly products are sold in over 120 countries around the world. Its most widely prescribed and consumed products are Prozac (despression and anxiety), Zyprexa (schizophrenia and bipolar disorder), Byetta (type 2 diabetes) and Cialis (erectile dysfunction).

History of Lilly

So the story goes, Colonel Eli Lilly, a veteran of the Civil War and the founder of the global pharmaceutical giant, started his humble drug company due to his alleged dissatisfaction with the quality of contemporary medicine in his day. One of the first drugs that Colonel Lilly produced was quinine, a drug for the treatment of malaria. Lilly was also known as an innovator for first coating pills and capsules with gelatin. Over the years, Lilly grew considerably and established a landmark manufacturing facility in its present-day headquarters in Indianapolis, Indiana. In the 1970s, Lilly hit $1 billion in sales for the first time. Today, Lilly employs over 40,000 people worldwide.

Lilly, Prozac and the Market for Psychiatric Medication:

Lilly is perhaps best known for production of the psychiatric drug Prozac (fluoxetine) the first Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) to arrive on the market in 1988. It is hard to overstate what a huge impact Prozac was both for Lilly and the booming market for psychiatric drugs. Soon after its introduction, Prozac was netting close to $1 billion a year in sales for Lilly. Suffice to say, Prozac went on to embed itself in popular culture and has come to be one of the most recognized drug names for the treatment of depression today.

Lilly and Issues with Dangerous Drugs:

As remarkable as Lilly’s history, growth and success over the past 150 years have proven, the company’s business and reputation have suffered in recent years from a string of issues arising from dangerous drugs pushed into the market. Some of the more notable cases to make headlines have arisen from:

Axiron

Marketed in 2011 as an underarm testosterone replacement gel for men, Axiron was billed by Lilly as an easy and effective method for treatment of low-testosterone levels. Due to a rash of studies in recent years, which have indicated that low testosterone may be responsible for a number of common ailments in older men – notably fatigue and loss of sexual ability, treatments to boost testosterone have become remarkably popular. Unfortunately, they also tend to be overprescribed and aggressively marketed at men who may not actually be suffering from low testosterone levels. Many men who began testosterone treatments, some under the most specious of circumstances, later began suffering increased risk from heart attacks, strokes and sudden death at a much greater rate than normal. Consequently, Lilly has been embroiled in lawsuits resulting from these complications and Axiron has been withdrawn from the market.

Actos

Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1999, Actos (pioglitazone hydrochloride) was a drug jointly-marketed by Lilly and pharmaceutical giant, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. The FDA issued a black-box warning for Actos in 2007 due to concerns over increased risk for heart failure associated with the drug. In 2011, the American Diabetes Association reported its findings that Actos could also be associated with increased risk for bladder cancer. Litigation against both Takeda and Lilly ensued culminating with verdicts against both companies totalling $9 billion for masking cancer risks associated with Actos.

Zyprexa

One of the more popular medications for treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar mania upon its introduction to the market, Zyprexa (olanzapine) was also frequently prescribed alongside of Prozac as “Symbyax”. In 2005, the FDA mandated that both drugs receive black box warnings for the risk of death from heart failure and various infections for elderly patients who were prescribed the drugs for the treatment of dementia (an off-label use, for which the FDA did not expressly approve the drug). Additionally, Lilly modified the label for Zyprexa in 2007 due to concerns about increased suicidal thoughts and ideation in children who were prescribed the medication. It should be noted that Zyprexa was never approved for use in patients under the age of 18 (another off-label use). In 2009, Lilly plead guilty and admitted that it illegally marketed Zyprexa as appropriate for elderly dementia patients and children despite not being approved for such use on its label by the FDA.

Tradjenta

A medication for type 2 diabetes, Tradjenta (linagliptin) is part of a larger family of drugs known as dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DDP-4) inhibitors. This family also includes other diabetic medications such as Januvia, Byetta and Victoza. Also known as mimetics, these drugs have been cited by the FDA for their increased risk of pancreatitis and related pre-cancerous cell changes. In 2013, the agency announced that it would be investigating the unpublished findings of several academic researchers who examined post-mortem tissue samples from patients for further evidence of the pancreatic linkage.

Sources Cited:

1) “About Lilly” https://www.lilly.com/who-we-are/about-lilly

2) “Novartis Takes Aim at Eli Lilly with Cosentyx FDA Nod in Spondyloarthritis” https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/novartis-takes-aim-at-eli-lilly-fda-nod-for-cosentyx-spondyloarthritis

3) “Eli Lilly pharmaceutical company starts Phase 3 coronavirus trial with drug used to treat arthritis” https://www.foxnews.com/health/lilly-starts-phase-3-coronavirus-trial-for-baricitinib-arthritis-drug

4) “Eli Lilly (LLY) Stock Sinks As Market Gains: What You Should Know” https://www.yahoo.com/news/eli-lilly-lly-stock-sinks-214509929.html

5) Eli Lilly and Company SEC Filings http://www.getfilings.com/sec-filings/160219/LILLY-ELI-and-CO_10-K/lly-20151231x10kexhibit21.htm

6) “25 Years After Prozac” https://www.pharmacist.com/25-years-after-prozac

7) “Selling Prozac at the Life-Enhancing Cure for Mental Woes” https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/22/us/selling-prozac-as-the-life-enhancing-cure-for-mental-woes.html

8) “Testosterone Treatment: Fountain of Youth or Heart Attack Risk?” https://www.indystar.com/story/money/2014/11/21/testosterone-treatment-fountain-youth-heart-attack-risk/70041122/

9) “Lilly Adds Strong Warning Label to Zyprexa, a Schizophrenia Drug” https://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/06/business/06zyprexa.html

10) “The Trouble with Zyprexa” https://pro.psychcentral.com/the-trouble-with-zyprexa/

11) “FDA Warns About Using Antipsychotic Drugs for Dementia” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC556368/

12) “Zyprexa Medication Guide” https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Zyprexa-Medication-Guide.pdf

Common Heartburn Medication Contains Probable Carcinogen

The FDA has recalled popular over-the-counter and prescription heartburn ranitidine drugs (or otherwise known as Zantac) due to unsafe levels of N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a probable human carcinogen. This recall came as a result of an ongoing investigation of NDMA discovered in ranitidine medications.

The investigation into NDMA

In the summer of 2019, it became known that low levels of this substance had been found in ranitidine medicine. Low-levels of this NDMA are often found in food products, but these low levels are not expected to increase the risk of cancer. High levels of exposure to NDMA do increase the risk. Upon discovering the possibility of NDMA in ranitidine, the FDA investigated whether these drugs form NDMA in the human body. The FDA warned the public about the possibility of NDMA in the medication back in September 2019 but did not have enough evidence to issue a mandatory recall. However, the FDA did request a voluntary recall and asked manufacturers to conduct their own laboratory testing and send samples to the FDA.

In April of this year, FDA testing confirmed NDMA levels increase in ranitidine drugs over time, even with normal storage conditions, especially the further the product gets from its date of manufacturing. Also, the NDMA levels increase when the drugs are stored at higher temperatures.

Many companies did voluntary recalls on the ranitidine products prior to this mandatory recall by the FDA. Sanofi recalled its over-the-counter Zantac in October of last year. Appco Pharma LLC and Northwind Pharmaceuticals did so in January. Many drug stores took action as well, including CVS and Walgreens, who stopped selling Zantac and other ranitidine drugs as of last year.

What to do if you are taking a rantinide drug (Zantac)?

Consumers are being advised to stop taking any current over-the-counter Zantac they currently have and switch to other approved over-the-counter heartburn medicines. For those on prescription Zantac, speak with their healthcare professional immediately about alternative options. When disposing of the medication, the FDA advises consumers and patients to follow the medication disposal information on the packaging included with the medication.

Several drugs that serve the same purpose as ranitidine drugs do not have the same risks from NDMA. At this point, only if a company can prove to the FDA that their ranitidine product is stable and that the NDMA levels do not increase to unsafe levels, will any be back on the market and available to patients and consumers. It’s always essential to stay up to date about the medication you are taking, so check in with the Drug Law Journal for ongoing news and up-to-date information.

How To Determine The Safety Of Children’s Over The Counter Cold Medications

As parents, we know that at some point our children will come down with a cold and we will need to be prepared to help them feel better quickly. Many people go through a variety of over the counter cold and flu medications in an attempt to find just the right remedy to give to their children. Figuring out which medication is right for their symptoms can be a confusing task riddled with possible implications that could have an impact on your child’s health.

What The FDA Recommends

Pharmacy shelves are packed full of pills and liquids claiming to ease the discomforts of a cold or cough, but as consumers, we are not versed in the ingredients and their possible side effects. Because of this, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has called for caution when it comes to over the counter cold medications.

These types of medications are no longer recommended for children under the age of four, and the FDA recommends that only under the advice of a physician should children between the ages of four and six take them.

The reasoning behind the FDA’s recommendation is due to the developmental growth of children, which impacts how their bodies are able to process certain medications. The American Academy of Pediatrics has endorsed these recommendations in an attempt to spare children from the unnecessary and potentially harmful medication related side effects.

Recalls Of Over The Counter Medications

In addition to the recommendations on over the counter cold medication use for children are the recalls of certain products. Infant Ibuprofen and Children’s Motrin have both undergone recalls of some form. This is not uncommon as oftentimes recalls can be administered to certain include an entire product or merely certain specific lots, typically being triggered by production processes and standards.

Staying On Top Of The Information

It is important to stay aware of the latest recalls and medical updates when you are choosing what medications to give your child. The Drug Law Journal publishes up to date information regarding all types of medical recalls, warnings, and findings, which makes it an outstanding online resource for parents who want to stay current on medical information that may affect their child’s health.

Keeping Your Child Healthy

Any medication you give your child should always undergo careful scrutiny, and it is imperative that instructions are carefully read in order to keep your child safe from harmful side effects. Making our children feel better when they are sick, however, keeping them safe and healthy is the top priority.

Updated Guidelines For Treatment of Adolescent ADHD

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has revised the guidelines for the care of children and adolescents diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) which offers clinicians updated information and opportunities as they work towards providing treatment plans for patients in their care.

Caring for patients with ADHD is complex, and according to the updated treatment models, occurs best in a patient-centered medical home. These new guidelines have been updated from 2011, and can serve as sources of current applications and information for primary care pediatricians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and family medicine practices.

Establishing the diagnosis, these guidelines are based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). While the DSM-5 guidelines are similar to those of 2011, there are two noteworthy exceptions. Fewer problem behaviors for those age 17 and over are required, and evidence that symptoms began before the age of 12 years instead of age 7.

Also remaining essentially unchanged are the recommended courses of treatments for ADHD. Stimulant medications amphetamines and methylphenidate in various forms are typically the initial approach to counteracting the symptoms of this disorder. Additions included an increase in the number of extended-release forms of stimulant medications, such as Atomexetine, which remains a secondary alternative medication.

Alpha-2 agonists guanfacine and clonidine also continue to be preferred methods of secondary alternative medications. These extended-release medications are also approved by the Food and Drug Administration as adjuvant treatments.

While behavior therapy is recommended as the first line treatment approach for preschoolers, it is noted in the new guidelines that descriptions of ‘behavior therapy’ for children remain vague, and more detailed treatment plans should be identified.

The predominant studies that were reviewed included recommendations for parents and caregivers that describe behavior management tactics for preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD. Valuing parent and teacher training in behavior management for high school aged children, several included studies outlined the importance of a continuum of care.

Additional concerns touch on the challenges that can be experienced by clinicians when seeking to implement these guidelines, including poor paediatric training in mental health, limited consultative services, and barriers to communication with schools.

The Drug Law Journal provides a wealth of information on updates to medical and mental health guidelines, pertinent information on drug recalls and lawsuits, and current treatment approaches for ADHD diagnosis as well as other health related topics. Staying informed and updated on current findings is an important piece of ensuring the best care is received.