Pre-Market Approval (PMA) is the name of the process the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) utilizes to review and evaluate the safety and effectiveness of medical devices which present a risk so great that ordinary regulatory controls are insufficient to guarantee their safety and effectiveness. PMA is the most stringent control the FDA has on medical device marketing, requiring applicants to supply copious amounts of valid scientific evidence prior to receiving approval from the agency.

Which Devices Are Required to Undergo PMA?

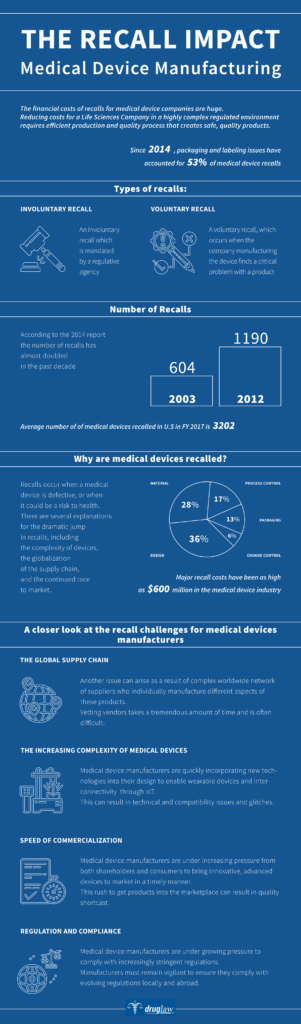

Medical devices are regulated by the FDA and can encompass a broad range of objects ranging from tongue depressors, to stethoscopes, lab equipment, surgical instruments and life supporting equiment such as ventilators. The FDA subjects “Class III” medical devices to PMA review. These are medical devices that support or sustain human life, or are substantially important for preventing impairment of human health, or themselves present a potential, unreasonable risk of illness of injury.

Agency approval of a PMA for a Class III device requires that the applicant establish a “reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness” with scientific evidence. What this means is that the FDA will be looking for whether the device’s probable benefits outweigh its probable risks; while examining results of studies for effectiveness. The evidence the FDA examines during the PMA process typically includes:

- Studies and Trials

- Case Histories

- Reports of Significant Human Experience

History of Premarket Approval

The FDA began regulating medical devices following the enactment of the 1976 Medical Device Amendments to the federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Prior to that point, medical devices were not required to undergo any sort or federal oversight and inspection. Instead, they were regulated by a patchwork of state consumer protection laws applicable to all different types of consumer products.

The Medical Device Amendments created three classes of medical devices based upon their risk to patients. Class I devices are considered “low risk” (i.e. bandages and stethoscopes), Class II are “medium risk” (i.e. blood pressure cuffs, peripheral vascular catheters); and Class III “high risk”. Class I devices are generally exempt from FDA review, requiring only registration and adherence to basic FDA standards and practices. Class II devices can usually bypass the PMA process if they are deemed “substantially equivalent” to a preexisting device cleared for marketing. This process is known as the 510k pathway and does not require the rigorous testing that PMA demands. Generally speaking, all Class III devices are required to be reviewed under the PMA process, although a select few have been permitted to bypass PMA through the 510k process, something which has attracted substantial criticism in recent years.

How Does the PMA Process Work?

PMA review is a complex process that extends over multiple layers of review once the application process commences. First, the device manufacturer or patent holder must submit an application for PMA to the FDA. The agency will then conduct a “limited scientific review” of the application to determine if it is suitable for filing. Once the FDA is satisfied with the application package, it will clear the device for more thorough and in-depth review. Next the FDA will begin a thorough investigation of scientific and clinical data submitted by the applicant, as well as examine quality systems and regulatory compliance. Following this intense review stage, the FDA may subject its findings to an outside panel of experts called an “Advisory Committee”, which will hold public meetings and submit a final report to the FDA. Finally, the FDA will convene for final deliberations, documentations and then notify the applicant of its decision. The timeframe from start-to-finish for PMA review is typically anywhere between 240-350 days.

User Fees

A substantial component to the PMA process involves the user fees charged to manufacturers. The FDA collects user fees for the review of original PMAs and supplements. In recent years, the cost of an original device application was in excess of $250,000. These amounts are adjusted approximately every 5 years by Congress.

What Happens After a Device is Approved Through the PMA Process?

Once a device receives approval through PMA, manufacturers may make incremental changes to a device design without re-submitting it again. These changes are regarded as part of the normal “product life cycle” and the deference accorded to devices in this respect is very different from the process for drug approval where any change to the active ingredient would require a completely new FDA authorization.

When a device manufacturer decides to make changes or “supplement” an approved design, they can do so through varied review processes. The most substantive changes to a device design undergo a “panel track” supplement review where an independent panel of experts oversees the process and reviews newly collected scientific and clinical data to support the supplemental application. Other major changes, such as an improved design element may be approved within a 180-day window supported by limited “pre-clinical” data. Minor changes to correct any post-approval issues, such as battery life, may be handled by a “real-time” review conducted by the FDA without any need for additional clinical data.

Any change which does not alter the device itself, such as a change to a manufacturing process, only requires notice to the FDA. Changes to the device’s label to address newly discovered safety concerns can be made through a “special supplement” process wherein the manufacturer can make the change prior to formal approval by the FDA.

What Are the Legal Implications of the PMA Process?

When Congress handed oversight of medical devices to the FDA, it included language in the legislation which “preempts” legal claims against approved device manufacturers under state law (where most product liability claims arise). This application of the preemption doctrine was further refined in 2008 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Riegel v. Medtronic that the PMA process specificially exempts approved manufacturers from state product liability tort claims.

It is worth noting however, that in the 1996 case Medtronc v. Lohr the Supreme Court did not extend the same preemption shielding to manufacturers who had bypassed the rigors of PMA, instead electing to seek approval under the 510k route. The court then reasoned that the “substantial equivalence” standard enumerated by the 510k process did not justify preeemption. Accordingly, only “high-risk” devices that run the PMA gauntlet are shielded from product liability claims.

Sources Cited (15)

“Premarket Approval (PMA)” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-submissions/premarket-approval-pma

2) “PMA Review Process” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-approval-pma/pma-review-process

3) “FDA’s Role in Regulating Medical Devices” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/home-use-devices/fdas-role-regulating-medical-devices

4) “An Overview of FDA Regulations for Medical Devices” https://www.einfochips.com/blog/an-overview-of-fda-regulations-for-medical-devices/

5) “Drugs, Devices, and the FDA: Part 2: An Overview of Approval Processes: FDA Approval of Medical Devices” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2452302X16300183

6) “FDA Authorization of Medical Devices” https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1817798

7) “U.S. Medical Device Clearance: Navigating the FDA 510k Premarket Approval Process for Medical Devices” https://legacy-uploads.ul.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/2015/02/UL_WP_Final_U.S.-Medical-Device-Clearance-Navigating-the-FDA-Premarket-Approval-Process-for-Medical-Devices_v5_HR.pdf

8) “FDA approval of cardiac implantable electronic devices via original and supplement premarket approval pathways, 1979-2012.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24449317

9) “How do Orthopaedic Devices Change After Their Initial FDA Premarket Approval?” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4773325/

10) “PMA Historical Background” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-approval-pma/pma-historical-background

11) “Approval of High-Risk Medical Devices in the US: Implications for Clinical Cardiology” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4080312/

12) “FDA Regulation of Dental Devices: Past, Present, and Future” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227820169_FDA_Regulation_of_Dental_Devices_Past_Present_and_Future

13) “The 510(k) ancestry of a metal-on-metal hip implant.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23301729

14) “User fees and beyond–the FDA Safety and Innovation Act of 2012” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23034017

15) “Life after Riegel: a fresh look at medical device preemption one year after Riegel v. Medtronic, Inc.” https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/foodlj64&div=19&id=&page=

U.S. Food and Drug Administration Approval Process

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is one of the nation’s oldest regulatory agencies and, among its responsibilities, it is charged with ensuring the safety and effectiveness of drugs and medical devices in the U.S. market. The FDA itself is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and its leader is the Commissioner of Food and Drugs (also known as the “FDA Commissioner”).

The FDA separates its regulatory responsibilities into two broader frameworks. First, the FDA will review data and studies to determine the safety and effectiveness of a submitted drug or device application prior to its entry into the market – also known as the “premarket approval” stage. Once a drug or device has passed the premarket threshold and is approved, the FDA continues to monitor each applicant through “postmarket” data submissions and performance studies.

Even though the FDA’s mission as well as the premarket and postmarket processes seem pretty straightforward, they are, in fact, riddled with regulatory, scientific and legal standards that give some wiggle room to both applicants and the FDA itself when determining whether a drug is safe and effective or whether a drug or device can bypass entire stages in the review process. For some approved drugs and devices, key safety concerns with life-altering consequences may only materialize or are discovered after these products have been on the market for years. Between 1993 and 2010, seventeen drugs were approved by the FDA and then later withdrawn. It is estimated that during this time, these drugs were prescribed over 112 million times. Nine of these drugs were prescribed more than 1 million times prior to market withdrawal.

Accordingly, in an age when commercials for over-the-counter and prescription drugs are everywhere on television, radio and the interest; and where family doctors are routinely pressured by manufacturers to prescribe their specific medications and devices; it is more important than ever for consumers to arm themselves with information about the possible side effects, potential for injury and other issues involved with FDA approved drugs and devices.

Overview of the FDA Drug Approval Process

All prescription drugs marketed within the United States must have approval from the FDA. In order to receive that approval, drug manufacturers must first demonstrate the safety and effectiveness in accordance with the laws and regulations administered by the FDA. Additionally, manufacturers are required to ensure that their manufacturing facilities pass FDA inspection and that all drug labeling is approved by the FDA.

Something most Americans probably don’t realize is that the development of the prescription medications they are prescribed on a daily basis often begins long before the FDA’s involvement. In fact, most research and development on new prescription drugs takes place in university, hospital and government laboratories, oftentimes funded entirely by the federal government itself. If this research yields a formula that looks promising, government and private research groups will then develop a prototype. If the prototype looks like it will be profitable drug idea or component, then private industry will pick it up and develop it further in anticipation of submission to the FDA for approval.

Investigational New Drug Application

Except under very limited circumstances, the FDA will require safety and effectiveness data from clinical trials. These trials are designed, conducted and analyzed in accordance with FDA standards and involve studies of human subjects. Prior to clinical trials, the drug manufacturer will file an Investigational New Drug (IND) application with the FDA. This application must include, among other things: data from animal trials; a description of what the drug does; and its intended use. The FDA will then review this application and within 30 days either object or approve the start of clinical testing.

Clinical Trials

Once the FDA authorizes IND status to a new drug, the manufacturer sponsor will assemble research on a smal number of human volunteers. “Phase I Clinical Trials” will attempt to ascertain:

- Dosage

- How a drug is metabolized and excreted

- Any acute side effects

After the manufacturer sponsor evaluates the results of Phase I, it will then decide whether to proceed to “Phase II and Phase III” trials to gather evidence of a drug’s effectiveness in a larger group of test subjects that possess the qualities or characteristics that the drug is designed to address.

New Drug Application

Following the completion of clinical trials, the manufacturer sponsor will submit a New Drug Application (NDA) to the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). The NDA will include previously submitted data about manufacturing assurances as well as:

A detailed product description

- Product indications (the diseases or conditions it treats)

- A proposed label

- A proposed Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).

Throughout the NDA review, the CDER will evaluate drug safety and effectiveness data, label accuracy, samples and inspect facilities where the finished product will be made.

Review of the NDA

While reviewing the NDA, the FDA will consider three larger questions:

- Is this drug safe and effective for its proposed use? Do the benefits of this drug outweigh its risks?

- Is the drug label appropriate and does it contain the proper information?

- Has the manufacturer instituted sufficient controls to maintain and ensure the drug’s quality, strength and purity?

In particular, FDA scientific and regulatory staff will prepare several assessments covering a wide range of medical, clinical and risk mitigation topics relevant to the applicant drug. The law requires that the FDA approve only after it has received “substantial evidence” of a drug’s safety and effectiveness. However, the FDA has flexibility in determining what it requires as evidence. It can rely on studies solely from those of the manufacturer itself or at its discretion include independent studies and evaluations in its review. Sometimes, the FDA will even convene an advisory panel of outside experts to review data, although the FDA is not bound by their recommendations. Once the FDA makes a final determination, the agency will send out either an approval letter or a “complete response letter” detailing where the NDA fell short of approval.

Generic Drugs and the Approval Process

In 1984, Congress passed the “Hatch-Waxman Act” which established an abbreviated pathway for so-called “generic” drugs. Specifically, it allows manufacturer sponsors to submit an “Abbreviated New Drug Application” or ANDA (as opposed to a full NDA). The ANDA allows the manufacturer to bypass the replication and submission of animal and clinical trial data – instead relying on the data submitted by the manufacturer sponsor from the original NDA. The ANDA must only demonstrate that the generic equivalent is pharmaceutically the same as the original “brand name” product submitted under the NDA.

Special Regulatory “Fast Tracking”

Drugs that address “unmet needs” or “serious conditions” or address other criteria associated with “improved public health”, the FDA uses several formal mechanisms to expedite the drug development and review process. Specifically:

- Fast Track and Breakthrough Products: Fast tracking does not necessarily mean a reduction in the data submitted by the manufacturer, as much as it compresses the time the agency takes to convene experts and meet to decide a drug’s NDA.

- Accelerated Approval/Animal Efficacy Approval: If a drug is deemed necessary, but human trials are not ethical or feasible, approval of a drug may be based on animal control studies alone.

- Priority Review: Again, this does not impact the data which must be submitted, but compresses the timeline for review by the FDA itself.

Over-the-Counter Drug Approval

Over-the-Counter (OTC) drugs are sold directly to consumers without a prescription. Like prescription medications, OTCs are regulationed by the FDA and treat many common ailments such as pain, fever, cough/cold and upset stomach. Because OTC drugs are taken outside of the supervision of a physician, they generally require a wider margin of safety for their routine use and labeling that ordinary consumers can understand. OTC drugs may be manufactured and sold without going through a standard NDA process. An OTC drug must only “conform” to an OTC monograph – a regulatory standard for the labeling of ingredients within the product.

Overview of the FDA Medical Device Approval Process

As with drugs, many medical devices must be reviewed bny the FDA prior to their being legally marketable in the United States. However, not all devices receive the same level of review and as American patients are finding out, lack of review and scrutiny can result in painful consequences and a lifetime of suffering.

The FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) bears primary responsibility for medical device review. Under U.S. law, all medical device manufacturers must register their manufacturing facilities and list their devices with the FDA. The FDA will then classify those devices on the basis of the risk they pose to patients: low; moderate or high. Moderate or high-risk devices must seek “pre-market approval” from the FDA with an application that assures the FDA of the device’s safety and effectiveness.

Standard Pre-Market Approval

The ordinary Pre-Market Approval (PMA) process is tightly controlled by the FDA. A PMA application is based upon the FDA’s determination that the manufacturer’s application contains sufficient valid scientific evidence to provide a “reasonable assurance” that the device is safe and effective for its intended use. Approval of a PMA requires that the FDA review copious clinical and scientific data about the device and how it will perform in human subjects. Additionally, the FDA may convene advisory panels to review and make recommendations based upon the submitted data. The approval timeframe for a full PMA can take months or years. In 2015, 98% of PMAs accepted for filing were approved by the FDA.

510(K) Notification

In contrast to the rigorous evaluation and application protocols within the PMA application process, the FDA will also allow some manufacturers of “moderate risk” devices to bypass the PMA altogether and fastlane products onto the market with comparatively little scrutiny. Using what is termed as the “510(k) Notification” or “510(k) Approval” pathway, manufacturers can submit new products which can trace their lineage back to a pre-approved product with only “minor” technical, design or performance changes – also known as “substantial equivalence”. Many 510(k) applicants trace their “substantial equivalence” lineage back to products which were approved by various state regulatory agencies before the FDA was given regulatory authority in the 1970s.

Between 1996 and 2009, more than 80% of the devices cleared by the FDA posed a “moderate risk” (Class II) and the General Accounting Office (GAO) found that 25% of the Class II devices implanted between 2003 and 2007 were either “implantable, life sustaining or presented a significant risk to the health safety and welfare of the patient”. It is worth noting that the FDA cleared 90% of 510(k) submissions reviewed during this same time period.

In 2008, an orthopaedic device made by ReGen, a New Jersey company, was cleared for market using the 510(k) process. In April 2009, the then-Acting FDA Commissioner initiated an internal review of the decision to clear the ReGen MenaFlex device. The FDA report that ensued provided a list of 22 instances wherein the FDA did not follow established processes, procedures or practices. The final report chalked up many of the issues at the FDA to broad “confusion” about the legal standards imposed by the 510(k) process.

Criticism of the 510(k) Process

At the behest of the FDA, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) studied the 510(k) process and produced a significant report with many suggestions and criticisms of the process. Overall, the IOM recommended that the 510(k) process be “replaced with an integrated premarket and postmarket regulatory framework that effectively provides a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness throughout the device life cycle”.

It is worth noting that the 510(k) process has not been duplicated elsewhere (in contrast to the FDA’s drug application system – which has been replicated in many other countries). Other countries continue to tightly regulate medical devices and do not rely on “substantial equivalence” to a previously approved device for market clearance.

Sources Cited (13)

1) “Development & Approval Process | Drugs” https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs

2) “The Drug Development and Approval Process” https://www.fdareview.org/issues/the-drug-development-and-approval-process/

3) “How are drugs approved for use in the United States?” https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/pharma/conditioninfo/approval

4) “How the FDA Approves Drugs and Regulates Their Safety and Effectiveness” https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R41983.pdf

5) “The FDA’s New Drug Approval Process: Development & Premarket Applications” https://drug-dev.com/fda-update-the-fdas-new-drug-approval-process-development-premarket-applications/

6) “NIH and FDA Announce Collaborative Initiative to Fast-track Innovations to the Public” https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-fda-announce-collaborative-initiative-fast-track-innovations-public

7) “A step-by-step breakdown of the FDA’s drug approval process” https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/supply-chain/a-step-by-step-breakdown-of-the-fda-s-drug-approval-process.html

8) “From Idea to Market: The Drug Approval Process” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11572541/

9) “The FDA approval process for medical devices: an inherently flawed system or a valuable pathway for innovation?” https://jnis.bmj.com/content/5/4/269

10) “FDA Regualtion of Medical Devices” https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42130.pdf

11) “Over 100 million prescriptions written before drug safety recalls” https://pnhp.org/news/over-100-million-prescriptions-written-before-drug-safety-recalls/

12) “FAQs About the Regulation of OTC Medicines” https://www.chpa.org/FAQsRegOTCs.aspx

13) “Facts About Generic Drugs” https://www.fda.gov/media/83670/download#:~:text=FDA%20requires%20generic%20drugs%20to,as%20the%20brand%2Dname%20drug.&text=Many%20generic%20drugs%20are%20made,as%20the%20brand%2Dname%20drugs.