The Stryker Corporation is a well-established and well-known manufacturer of a range of medical devices on the market in the United States today. Over recent decades, the company has positioned itself to be a prominent player in the hip and knee-joint replacement category with several popular joint replacement products. Some have gone on to be huge successes for Stryker, while others, such as the Rejuvenate, ABG II, and LFIT 40 lines became the objects of controversy and later – lawsuits; due to high rates of revision surgery and metal contamination.

History and Background of Stryker

Stryker is a specialty medical equipment manufacturer that designs, develops and manufactures surgical and health care products. From its headquarters in Kalamazoo, Michigan, it has grown to become one of the world’s largest medical technology companies with product lines spanning:

- Orthopaedic Implants

- Orthopaedic Trauma Systems

- Endoscopic Systems

- Patient Care Technologies

Stryker was established in 1941 by Dr. Homer Stryker, an orthopaedic surgeon from Kalamazoo who was dissatisfied with the medical products he encountered in those days. Immediately, he and his company set out to design newer and improved devices to replace the ones that he deemed were ineffective or inefficient. His first successful device was the “Stryker Frame” – a mobile hospital bed which pivoted easily. A common sight in hospitals even today, Stryker beds allow doctors to shift injured patients while keeping them immobilized.

Under the tenure and watch of Dr. Stryker and his son, Lee, Stryker grew steadily through the 1950s and 1960s. However, it wasn’t until the 1970s and the arrival of Stryker’s new CEO, John Brown (formerly of Bristol Myers Squibb) that the company launched down the path of explosive growth that characterizes Stryker to this very day. Over the 32-year span of John Brown’s career at Stryker, he took the company public (1979) and turned Stryker into a perennial favorite of the Fortune 500.

Today, Stryker sells its products in over 100 countries, owns nearly 5,000 patents globally, and has 33,000 employees worldwide. In 2015 it boasted 36 years of straight sales growth and $9.9 billion in sales revenue. Hip implants from its Howmedica Osteonics division, which it purchased from Pfizer Inc., in 1998 for $1.9 billion in cash, accounted for 13% of sales in 2015 alone. Orthopedic implants account for 43% of Stryker’s sales and it maintains a position within the top three manufacturers globally for knee and hip implants – a 22% market share for these devices.

Issues with Stryker Hip Implant Technologies and Product Lines

Accolade, ABG II and Rejuvenate Systems

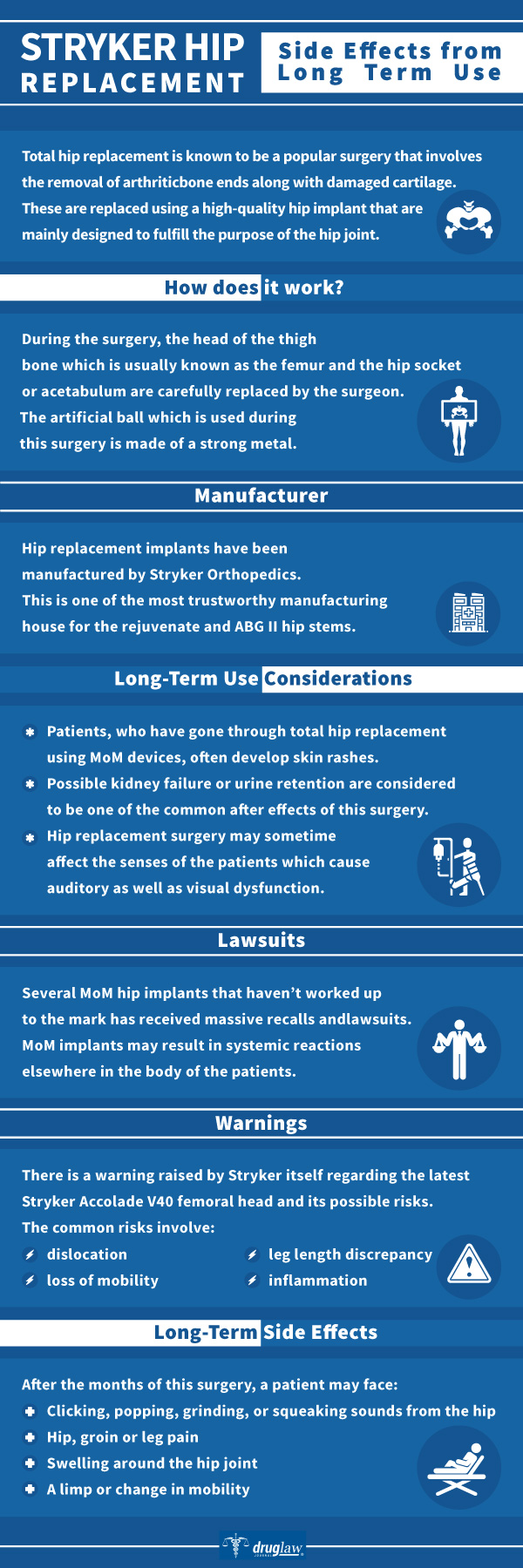

The Accolade, ABG II and Rejuvenate hip joint systems were all designed and manufactured by Stryker’s Howmedica Osteonics business unit to utilize a proprietary alloy known as “TMZF” (Titanium/Molybdenum/Zirconium/Iron) which, it was believed, would better approximate the elastic properties of bone, while allowing for increased flexibility and strength.

The Accolade system was presented and marketed as a total hip femoral stem for coupling with Stryker’s other proprietary femoral head technologies. Alternatively, the Rejuvenate and ABG II were marketed as femoral stem “modular” component systems with varying sizes of stems (right and left) as well as modular necks. Both sets of device lines utilized TMZF in the stem while ABG II also incorporated a cobalt-chromium alloy into the neck.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the Rejuvenate and ABG II lines for sale in the United States in 2008 and 2009 respectively. Both devices were reviewed under the FDA’s 510(k) clearance process without requiring any extensive studies, clinical trials or pre-market testing prior to implantation in patients. Almost immediately, surgeons and patients started noticing issues with the devices associated with corrosion and fretting at the modular neck-joint. Neck failure and corrosion frequently necessitated expensive and painful revision surgeries and were accompanied by: metallosis; bone necrosis; pseudotumors and acute metal toxicity in the blood.

Both the Rejuvenate and ABG II product lines were recalled in July 2012. Subsequently, Stryker completely eliminated the TMZF alloy from its entire product lineup.

LFIT V40 Femoral Heads

The LFIT V40 femoral head is the “ball” component which was configured more broadly into the overall Stryker TMZF “stem” product line beginning in the early 2000s. Specifically, the femoral head fits neatly into the bone socket of the pelvis and allows freedom of rotation. These devices were marketed ostensibly as a way of minimizing dislocation issues for patients.

In 2016, an investigative report issued by a prominent medical journal concerning issues involving metallic debris and damage to soft tissue stemming from corrosion and wear on the LFIT V40. Not long afterward, Stryker released an urgent “medical device notification” to the surgical community, then recalled nearly 42,000 units of the LFIT V40 due to concerns over the potential for hip dislocation and metallosis.

Tritanium Acetabular Shell

In 2008, Stryker introduced a porous 3D-printed acetabular cup made from Tritanium alloy marked under its “Trident” line. It later introduced its “next-generation” version of the Trident II cup in 2018. The design of the Trident line allows for large femoral head size options and a greater range of motion. According to Stryker, the Trident promises greater joint stability and lower risk of dislocation, while the porous surface is intended to mimic the characteristics of pelvic cancellous bone.

Stryker itself funded a 2013 follow-up study which reviewed the Total Hip Arthroplasties (THA) of 252 patients who received the Tritanium cup. The study, which was conducted, in part, by authors who were receiving royalties from Stryker or had preexisting financial relationships with Stryker, triumphantly reported that 100% of the implants were still successful 25-56 months following surgery.

However, independent studies published between 2017 and late 2018 have uncovered concerns about the safety and effectiveness of the primary Tritanium acetabular cups. Indeed, a study conducted at the NYU Langone Hospital, which was published in 2018, reported that five revision patients who were implanted with the primary Tritanium acetabular cup had failed to achieve “bone-in growth” following THA procedures between 2011 and 2016. At least two other contemporary studies have uncovered similar findings.

What these studies implicate in the primary Tritanium acetabular cup is a “loosening” because of its failure to encourage bone growth following implantation. This bone growth is essential to keeping the cup in place following THA. Consequently, patients loosening may experience pain and swelling; or worse yet – instability (“hip-locking”) or even dislocation.

Sources Cited (21)

1) “Stryker: Our History” https://www.stryker.com/us/en/about/history.html#nineteenthirty

2) “Stryker Fact Sheet” https://www.stryker.com/content/dam/stryker/about/about_landing/pdfs/2016_Fact_Sheet.pdf

3) “Stryker Corporation Backgrounder/Reuters” https://www.reuters.com/companies/SYK

4) “Stryker Corporation History” http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/stryker-corporation-history/

5) “Early aseptic loosening of the Tritanium primary acetabular component with screw fixation” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5994600/

6) “Corrosion-wear of β-Ti alloy TMZF (Ti-12Mo-6Zr-2Fe) in simulated body fluid” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27397494/#:~:text=Statement%20of%20significance%3A%20TMZF%20is,modular%20design%20total%20hip%20replacement.

7) “The Accolade TMZF stem fulfils the demands of modern stem design: Minimum 5-year survival in a cohort of 937 patients” https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2309499018807747

8) “ABG II Modular Anatomic Reconstruction” https://www.hpcbd.com/ABG-II-Modular-Rationale-and-Surgical-Technique.pdf

9) “Stryker Orthopaedics Launches the Rejuvenate Modular Primary Hip System” https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/stryker-orthopaedics-launches-the-rejuvenate-modular-primary-hip-system-83884277.html

10) “Stryker to Purchase Howmedica” https://www.meddeviceonline.com/doc/stryker-to-purchase-howmedica-0001

11) “Stryker Adds More Units to LFIT V40 Femoral Head Recall” https://newyork.legalexaminer.com/health/medical-devices-implants/stryker-adds-more-units-to-lfit-v40-femoral-head-recall/

12) “3 RECENT STUDIES QUESTION TRITANIUM ACETABULAR CUP SURVIVAL RATE” https://ryortho.com/breaking/3-recent-studies-question-tritanium-acetabular-cup-survival-rate/3/

13) “Stryker Launches Next Generation Trident® II Acetabular System” https://www.stryker.com/us/en/about/news/2018/stryker-launches-next-generation-trident–ii-acetabular-system.html

14) “Trident® Tritanium™ Acetabular System Surgical Protocol” https://www.strykermeded.com/media/1154/trident-tritanium-acetabular-system-surgical-protocol.pdf

15) “Tritanium Acetabular Cup in Revision Hip Replacement: A Six to Ten Years of Follow-Up Study” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29685709/

16) “Short to Midterm Follow-Up of the Tritanium Primary Acetabular Component: A Cause for Concern” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27642044/

17) “Comparison of a highly porous titanium cup (Tritanium) and a conventional hydroxyapatite-coated porous titanium cup: A retrospective analysis of clinical and radiological outcomes in hip arthroplasty among Japanese patients” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30055877/

18) “Early results of a new highly porous modular acetabular cup in revision arthroplasty” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19876878/

19) “Tritanium acetabular wedge augments: short-term results” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4930514/

20) “Medical Device Maker Accused in Marketing Fraud” https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/29/business/29device.html

21) “Sales Reps May Be Wearing Out Their Welcome In The Operating Room” https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/11/23/659816082/sales-reps-may-be-wearing-out-their-welcome-in-the-operating-room

Hip Replacements

Lawsuits and Legal Update

Last Updated September 12, 2020

Over the past few decades, hip replacement surgery, or Total Hip Arthroplasty, to repair hip-joints, often damaged by osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and traumatic arthritis, has become a commonplace procedure within hospitals and ambulatory surgical centers across the United States. Going forward, it is expected that the market for hip-joint replacement will dramatically expand. Due to a combination of the aging population trend and an explosion in robotically-assisted surgery, experts anticipate that the market for hip replacement devices will leap to $10.51 billion annually by 2026. Numbers like this are not lost on device manufacturers. Companies like DePuy (a Johnson & Johnson business unit), Stryker, Smith & Nephew, and Zimmer devote considerable resources and capitalization toward rapid development of newer hip-joint products in order to ensure that they capture a significant share of this highly profitable market.

With that in mind, the ability of these companies to rapidly develop and deploy new hip-joints rests squarely on navigating the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pre-market approval process, and in particular its 510(k) Clearance process. If a new medical device product can be proven to be “substantially equivalent” to another previously-approved product line, then the 510(k) process allows that manufacturer to bypass the ordinary safety and effectiveness testing rigors involved with standard pre-market approval.

Starting in the early 2000s, several manufacturers aggressively marketed hip-joints through the 510(k) process featuring a “Metal-on-Metal” (MoM) coupling feature between the ball and socket of the joint. In MoM joints, the metal ball and metal cup slide against each other during walking or running. This friction between the ball and socket can cause the release of metal particles that will wear off of the device and embed in surrounding tissue as well as metal ions of cobalt and chromium entering the bloodstream. Over time, this leaching of metal from the joint into surrounding tissue causes “Adverse Local Tissue Reaction” (ALTR) and/or “Adverse Reaction to Metal Debris” (ARMD). The bottom line for patients implanted with MoM joints, however, is that they suffer damage and pain, device failure, loosening, and the need for revision surgery. Furthermore, patients implanted with MoM hip joints can also suffer from a condition known as “metallosis” – a potentially fatal complication arising from metallic erosion in the joint which induces pain around the joint, pseudotumors, and a noticeable rash.

By 2010, the issues with MoM were becoming apparent to both the manufacturers and the FDA alike. The first MoM joint recall involved the DePuy ASR followed by market withdrawals of the Biomet Magnum M2A and others. Lawsuits soon followed and between 2013 and the present, billions of dollars in verdicts and settlements were racked-up over these devices. Currently, there are six active multidistrict litigation (MDL) cases involving hip-joint devices and their manufacturers, taking place in federal courthouses across the country with nearly 11,800 claimants in various stages of progress – and a possible seventh on the way. Some of these cases have resulted in verdicts and settlements in the hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars.

Historic Hip Joint Lawsuits, Recalls, Verdicts, and Settlements:

DePuy ASR XL Acetabular System and ASR Hip Resurfacing Resurfacing Platform (MDL-2197)

DePuy manufactured the ASR Hip Implant Device line and is a business unit of the global device giant, Johnson & Johnson. The ASR XL Acetabular System was made up of three components:

- The metal femoral stem inserted inside of the femur.

- The metal femoral head (or ball) connected to the stem; and

- The metal acetabular cup (socket).

Similarly, the ASR Hip Resurfacing Platform involves a metal cap placed over the natural femoral head and replacing the acetabulum with a metal cup.

Beginning in 2008, the FDA started receiving approximately 400 complaints from patients in the United States who were implanted with the devices. These patients complained of pain, swelling, inflammation, and damage to the bone and tissue – as well as a lack of mobility. Many of these patients required expensive and painful revision surgeries.

In 2010, DePuy issued a voluntary recall of ASR Hip Implant Devices and the first lawsuits naming DePuy soon followed thereafter. The cases were consolidated into an MDL and between 2013 and 2017, DePuy paid nearly $4.8 billion to settle approximately 7,500 cases.

It has been over ten years since the original ASR recall. And although this MDL is technically still open, settlement protocols have a stipulated deadline for potential litigants requiring a revision surgery to have been performed no later than July 2017.

DePuy Pinnacle Hip Replacement System with TrueGlide Technology (MDL-2244)

The DePuy Pinnacle Acetabular Cup System was launched in 2001 and offered the option of either a polyethylene or metal insert for use with a titanium cup to replace the natural hip socket. This was followed by the launch of the Pinnacle system coupled with TrueGlide technology in 2007.

Although the Pinnacle system was not subject to recall, patients still reported many of the same issues as those suffering with the DePuy ASR devices. Issues with loose implants, inflammation, swelling and damage to surrounding tissue coupled with the spread of metal debris and contamination throughout the body were not infrequent. Many patients implanted with Pinnacle devices suffered loss of mobility and went through painful and expensive revision surgeries in an attempt to correct issues.

Lawsuits involving the Pinnacle Hip Replacement System were aggregated into an MDL in a federal courtroom in Texas. In 2016, the second bellwether case in the MDL yielded a verdict in favor of the claimants to the tune of $502 million (later reduced under Texas law limiting punitive damages). A third bellwether case resulted in a $1 billion verdict in favor of claimants (reduced to $543 million on appeal) and a fourth bellwether case wound up with a $247 million verdict in favor of claimants.

In June 2019, DePuy announced that it would settle up to 6,000 of the Pinnacle lawsuits for $1 billion. DePuy is settling each case individually and as a consequence, this MDL remains open with up to 9,155 cases still pending.

Stryker Rejuvenate and ABG II Hip Replacements (MDL-2441)

Howmedica Osteonics Corporation, under the market name, Stryker, designed, developed, and marketed the Rejuvenate and ABG II MoM hip replacement devices. In 2012, Stryker recalled the Rejuvenate system due to issues with fretting and corrosion at the modular-neck junction. Following the recall, patients came forward with lawsuits, and these were consolidated into an MDL in Minnesota.

Between 2014 and 2016, Stryker settled the bulk of these cases for an estimated $1.4 billion. Despite the settlement, the MDL remained open well into 2020 with over 360 cases still pending.

Stryker LFIT V40 Femoral Head (MDL-2768)

Starting in 2000, Stryker marketed its MoM Accolade hip replacement system to hospitals and surgeons which involves two crucial components: the TMZF Hip Stem and LFIT Anatomic V40 Femoral Head. It is called a “monoblock” or single-piece artificial hip replacement device that utilizes a proprietary titanium alloy consisting of titanium, molybdenum, zinc, and iron.

Following a 2016 investigative report in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, which reported on issues involving corrosion in the V40 head as well as metallic debris and damage to the soft tissue, Stryker issued a recall of LFIT V40 heads. Lawsuits from implant patients suffering from metallosis and other issues associated with the LFIT V40 were then aggregated into an MDL in Massachusetts. In 2018, a confidential settlement was announced and individual cases are still being settled. Accordingly, this MDL remains open in 2020 with over 500 cases still pending.

Current Hip Joint Lawsuits

Smith & Nephew, Inc. Birmingham Hip Resurfacing System (MDL-2775)

In 2006, United Kingdom-based Smith & Nephew introduced the MoM Birmingham Resurfacing (BHR) system. A prosthesis, the BHR is comprised of two components:

- The Birmingham Resurfacing Femoral Head; and

- The Birmingham Resurfacing Acetabular Cup.

The FDA order allowing Smith & Nephew to market the BHR in the United States required the company to comply with several post-market survey and reporting practices relaying knowledge of adverse reactions, injuries or issues with the device, back to the FDA. Claimants in litigation pending before a Maryland federal court allege that Smith & Nephew in fact knew about a multitude of common MoM issues and adverse reports involving the BHR but either delayed reporting them to the FDA, underreported them or did not report them properly at all.

This MDL is still active and in its early stages. The first bellwether trials have been scheduled to commence in May 2021 and July 2021.

Zimmer M/L Taper Hip Prosthesis and Versys Femoral Head (MDL-2859)

Indiana-based Zimmer Biomet Holdings, Inc. developed and marketed the Zimmer M/L Taper hip implant with its proprietary Kinectiv Technology. This model of the M/L Taper with the Kinectiv technology utilized a modular MoM design that featured a cobalt-chromium coupling. In court documents, claimants allege that the Zimmer hip joint suffers from corrosion which introduces metal fragments into surrounding tissue as well as elevated levels of metals into the bloodstream causing pain, swelling, tissue necrosis, and other ailments.

This MDL is currently in its early stages and new cases are being added.

Bearing Scrutiny:

Stryker Tritanium Acetabular Shell

Stryker received clearance from the FDA to market its Tritanium Acetabular Cup in 2008 and later in 2011, received further clearance for a Tritanium Acetabular Shell with “Peri-Apatite” coatings on the bone-implant interface. Specifically, this coating added a “Particle Sintered Foam” (PFS) coating overlaid with Peri-Apatite.

In 2017, the journal Arthroplasty Today published an article on behalf of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons which delved into the cases of five patients who underwent revision surgeries for loosening issues with Stryker’s tritanium acetabular cups resulting in groin and hip pain. A 2018 article in Orthopaedic Proceedings which evaluated 121 revision surgeries involving Stryker tritanium devices made similar findings of premature deterioration in the hip joint.

New legal complaints naming Stryker and alleging design defects in the Tritanium Acetabular Shell line were filed in state court in New Jersey in 2019 and are currently pending further action.

Sources Cited (30)

1) “Hip Replacement” https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/hip-replacement/about/pac-20385042

2) “$502 Million Dollar Verdict Against Johnson & Johnson In DePuy Pinnacle Hip Implant MDL” https://www.expertinstitute.com/resources/insights/502-million-dollar-verdict-against-johnson-johnson-in-depuy-pinnacle-hip-implant-mdl/#:~:text=The%20jury%20in%20this%20bellwether,%24360%20million%20in%20punitive%20damages.

3) “Lessons Emerging from Pinnacle Hip Bellwether Trials” https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=e8bb3be1-5777-48b8-a31f-3b9757ff2541

4) “In re: DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc. Pinnacle Hip Implant Products Liability Litigation” https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=e8bb3be1-5777-48b8-a31f-3b9757ff2541

5) “U.S. ASR Hip Settlement” https://www.usasrhipsettlement.com/

6) “Stryker Reaches Settlement in Some LFIT V40 Cases” https://newyork.legalexaminer.com/health/medical-devices-implants/stryker-reaches-settlement-in-some-lfit-v40-cases/

7) “In re: M/L Taper Hip Prosthesis with Kinectiv Technology and Versys Femoral Head Product Liability Litigation” https://ecf.jpml.uscourts.gov/doc1/8501947622

8) “Johnson & Johnson to Settle Hip Lawsuits for About $1 billion, Sources Say” https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-johnson-johnson-settle-pinnacle-metal-hip-implant-20190507-story.html

9) “Metal-on-metal: history, state of the art (2010)” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3032111/#:~:text=Typically%2C%20the%20first%20total%20hip,generation%20metal%2Don%2Dmetal.

10) “Hip Replacement Market to reach USD 10.51 Billion by 2026, Increasing Prevalence of Osteoarthritis to Boost Market, Predicts Fortune Business Insights” https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2019/12/09/1957817/0/en/Hip-Replacement-Market-to-reach-USD-10-51-Billion-by-2026-Increasing-Prevalence-of-Osteoarthritis-to-Boost-Market-Predicts-Fortune-Business-Insights.html

11) “Linda Kay Benton v. Howmedica Osteonics Corporation” https://aboutlawsuits-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019-08-14-Complaint.pdf

12) “Hackett et al. v. Zimmer et al.” https://dockets.justia.com/docket/new-york/nysdce/1:2018cv10008/503738

13) “Sidney Rand v. Smith & Nephew, Inc.” https://www.pacermonitor.com/public/case/20177794/Sidney_Rand_v_Smith_and_Nephew,_Inc

14) “Grace Purnia v. DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc.” https://dockets.justia.com/docket/texas/txndce/3:2011cv01176/206705

15) “d’Orlando v. Howmedica Osteonics Corp. et al” https://www.pacermonitor.com/public/case/19786977/DOrlando_v_Howmedica_Osteonics_Corp_et_al

16) “Brigham v. DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc. et al” https://dockets.justia.com/docket/california/candce/3:2010cv03886/231266

17) “Bernard G. Owen v. Howmedica Osteonics Corporation et al.” https://www.law360.com/cases/51d20a72fb000b7dcf00956b

18) “MDL2768: In Re: Stryker LFIT V40 Femoral Head Products Liability Litigation” https://www.mad.uscourts.gov/worcester/MDL2768/MDL2768.htm

19) “DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc., ASR Hip Implant Products Liability Litigation” https://www.ohnd.uscourts.gov/mdl-2197

20) “In re Smith & Nephew Birmingham Hip Resurfacing (BHR) Hip Implant Products Liability Litigation (MDL No.2775)” https://www.mdd.uscourts.gov/re-smith-nephew-birmingham-hip-resurfacing-bhr-hip-implant-products-liability-litigation-mdl-no2775

21) “Stryker Rejuvenate and ABG II Hip Implant Products Liability Litigation, MDL No. 2441” https://www.mnd.uscourts.gov/content/stryker-rejuvenate

22) “Metal-on-Metal Hip Arthroplasty: A Review of Adverse Reactions and Patient Management” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4598667/#:~:text=Metal%2Don%2Dmetal%20relates%20to,metal%20acetabular%20cup%20or%20liner.

23) “NIH researchers uncover clues related to metal-on-metal hip implants” https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-researchers-uncover-clues-related-metal-metal-hip-implants

24) “Metal-on-metal hip replacements: implications for general practice” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5697529/

25) “What is appropriate surveillance for metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty patients?” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5810829/

26) “Metal ion levels comparison: Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing vs total hip arthroplasty in patients requiring revision surgery” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6180337/

27) “Management of metal-on-metal hip implant patients: Who, when and how to revise?” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4865716/

28) “Heavy Metal? Recognizing Complications of Metal on Metal Hip Arthroplasty” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4158987/

29) “Management Guidelines for Metal-on-metal Hip Resurfacing Arthroplasty: A Strategy on Follow Up” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5525522/

30) “Outcomes of a metal-on-metal total hip replacement system” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4473440/

Preemption Doctrine

For sufferers of the side-effects of dangerous drugs and medical devices, the journey to justice and seeking compensation for injuries is not always a straightforward one. Unfortunately, some claims for injury can be thwarted at the very outset due to a complex legal policy enshrined in Article VI of the U.S. Constitution – the “Supremacy Clause”. Known as the “Preemption Doctrine” it shields some manufacturers of approved drugs and devices from liability arising from the claims of victims.

What is Preemption?

“Preemption” describes the legal basis for dismissal of a claim under state law where the courts hold that federal law reigns supreme and invalidates state law. In essence, where state laws run contrary to or otherwise interfere with federal law, the federal will preempt the state law thereby excluding those claims.

How Does Preemption Apply to Drug and Device Manufacturers?

Prescription Drugs and Medical Devices are regulated under a federal law known as the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is charged with primary enforcement responsibility and to regulate drug and device manufacturers under the FDCA. To that end, the FDA has created an elaborate “pre-market approval” process designed to examine the safety and effectiveness of drugs and medical technology covered by the law. Over the past two decades, the existence of the FDCA has been used by drug and device manufacturers to argue that they cannot be sued on claims arising under state law.

When Does Preemption Become a Factor?

Preemption usually crops up as a defense by drug and device manufacturers against claims for injury made under state law. Manufacturers will point to the state law claims and say that because their products are regulated by the FDA and have gone through the federal “pre-market approval” process, they should be shielded from state law claims. And sometimes this strategy works – preemption does prevent some sufferers from mounting an effective case in court. But as the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled over the past two decades, preemption can’t stop every drug and device case and that is an important distinction for sufferers of side effects from dangerous drugs and devices.

Medical Device Lawsuits and Preemption

The FDCA sets down a detailed set of rules and standards which are designed to ensure that approved medical devices are safe and effective (the pre-market approval process). Part of the pre-market approval process involves certification and testing to make certain each submitted device meets minimum requirements before it is marketed to consumers and the healthcare industry in the United States. It goes without saying that the medical device pre-market approval process is rigorous, detailed and lengthy. Furthermore, the FDCA creates an explicit preemption rule for medical devices which have done through pre-market approval.

However, not every medical device is subjected to this rigorous process. Many medical devices on the market today and which have been implanted in patients throughout the United States can bypass the more detailed pre-market process and opt instead for the “Pre-Market Notification” or Section 510(k) Process. Essentially, these devices can avoid layers of FDA scrutiny and go straight into use.

With this in mind, the U.S. Supreme Court has made at least two critical rulings about the preemption defense and its use:

510(k) Approval Does Not Shield the Manufacturer – Medtronic v. Lohr:

In 1990, Lora Lohr’s Medtronic pacemaker failed, allegedly according to a defect. Lohr and her spouse filed a Florida state-court suit, alleging both negligence and strict-liability claims. The device at the center of Lohr’s claims made it to market through the markedly less rigorous 510(k) process. The state court dismissed Lohr’s claims ruling they were preempted. However, on appeal in 1996, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the lower court and established that medical devices that go through the 510(k) process, instead of the more rigorous pre-market process, cannot hide behind a preemption defense.

Premarket Approval Preempts – Riegel v. Medtronic:

During Charles Riegel’s angioplasty, his surgeon used an Evergreen Balloon Catheter to dilate his coronary artery. The catheter burst, causing extreme complications. Riegel sued the manufacturer, Medtronic, for negligence in the design, manufacture, and labeling of the device. Lower courts agreed with Medtronic that the corporation was shielded from Riegel’s state claims because the device in question was subjected to the more rigorous pre-market approval process and therefore enjoyed an explicit preemption defense under the federal law. The U.S. Supreme Court later affirmed this ruling.

Pharmaceutical Drugs and Preemption

Under the FDCA and subsequent amendments to the law, drug manufacturers have to file a New Drug Application (NDA) with the FDA before marketing a new drug. This NDA must contain detailed information about the drug’s composition, safety and effectiveness. The FDA will not approve a new drug if it finds that the drug is unsafe or ineffective – for use under the conditions prescribed, recommended or suggested on the label. Once approved, drug manufacturers must continue to monitor and report anything about the drug’s use which would compromise its safety, effectiveness or labeling.

Under the FDCA and subsequent amendments to the law, drug manufacturers have to file a New Drug Application (NDA) with the FDA before marketing a new drug. This NDA must contain detailed information about the drug’s composition, safety and effectiveness. The FDA will not approve a new drug if it finds that the drug is unsafe or ineffective – for use under the conditions prescribed, recommended or suggested on the label. Once approved, drug manufacturers must continue to monitor and report anything about the drug’s use which would compromise its safety, effectiveness or labeling.

Unlike medical devices, however, drugs do not enjoy an explicit presumption of preemption under the FDCA. And this has led to a range of divergent court opinions over the years.

Approved Drug Label Does Not Shield the Manufacturer – Wyeth v. Levine

Diane Levine had Phenergan, a drug made by Wyeth and used to prevent allergies and motion sickness, intravenously injected into her arm, and complications arising from the injection eventually led to the amputation of her arm. Ms. Levine sued Wyeth asserting that the company failed to include a warning label describing the possible arterial injuries that could occur from negligent injection of the drug. Wyeth argued that because their warning label had been deemed acceptable by the FDA, a federal agency, any Vermont state regulations making the label insufficient were preempted by the federal approval. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed with Ms. Levine asserting that the Wyeth bore ultimate responsibility for the content of its labels – at all times. The Court also rejected Wyeth’s preemption argument and reasoned that Congress did not intend to preempt state-law in failure to warn actions when it created the FDCA.

Generic Drugs Distinguished from Brand-Name Drugs – PLIVA v. Mensing

Gladys Mensing took the drug metoclopramide for four years to help fight diabetic gastroparesis. She filed a lawsuit against the generic drug’s manufacturers and distributors, contending that the drug gave her a severe neurological movement disorder, tardive dyskinesia, but none of the generic drug’s manufacturers and distributors made any effort to include warnings on the label. The manufacturers of this generic labeled drug claimed that Ms. Mensing’s claims were preempted under federal law. A lower court and the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with the drug manufacturers on the basis that generic drugs are manufactured under a label submitted by another manufacturer. To require generic drug manufacturers to change that label would result in a violation of federal law. A subsequent case: Mutual Pharmaceutical v. Bartlett extended this preemption shield on generic drugs further by also preempting claims other than “Failure to Warn”.

Sources Cited (13)

1. “Preemption of Drug and Medical Device Claims: A Legal Overview”, Congressional Research Service Report, September 2013. https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R43218.html#_Toc366593212

2. “Federal Preemption 19”, Richard A. Epstein and Michael S. Greve (2007).

3. “Unmasking the Presumption in Favor of Preemption”, Mary J. Davis, 53 S.C. L. Rev. 967 (2002) https://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1270&context=law_facpub

4. “The Tort Liability Insurance System and Federalism: Everything in its Own Time”, Roger C. Henderson, 38 Ariz. Law Review 953 (1996). https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/arz38&div=48&id=&page=

5. “Economic Analysis of Accident Law 298”, Steven Shavell (1987). https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvjghx2b

6. “The Economic Structure of Tort Law 9-12”, William M. Landes & Richard A. Posner (1987). https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5216&context=fss_papers

7. “Orphan Drugs: The Question of Products Liability”, Susan F. Scharf, 10 Am.J.L. and Med. 491 (1985). https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/amlmed10&div=34&id=&page=

8. “The Products Liability Resource Manual 135”, James T. O’Reilly and Nancy C. Cody (1993).

9. “The Fall of the Citadel (Strict Liability to the Consumer)”, William L. Prosser, 50 Minn. L. Rev. 791 (1966). https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3558&context=mlr

10. “The Battle of Implied Preemption: Products Liability and the FDA”, Mary J. Davis, 48 B.C. Law Rev. 1089 (2007). https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/44/

11. “Federalism in Action: FDA Regulatory Preemption in Pharmaceutical Cases in State Versus Federal Courts”, Catherine M. Sharkey, 15 J.L. & Pol’y (2007). https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/jlp/vol15/iss3/19/?utm_source=brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu%2Fjlp%2Fvol15%2Fiss3%2F19&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages

12. “Does the U.S. Constitution Constrain State Products Liability Doctine?”, Lars Noah, 92 Temple L. Rev. (2019). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3238093

13. “A Shift in the Preemption Landscape?”, Douglas G. Smith, Tennesee Law Review (2019). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3406918

Legal Relief & Compensation for Drug and Medical Device Injuries

Given the advanced nature and reach of our medical system, it should come as no surprise that the United States is home to the most prescription drug and medical device consumers in the world. Drug and medical device manufacturers spend billions of dollars every year marketing their products to physicians, patients, hospitals and clinics. To be sure, in many cases, these drugs and devices have the potential for tremendous good and benefits to the patients who consume or use them. However, in some cases, despite testing and review by authorities such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), these drugs and devices can cause severe pain, illness or life-altering injuries and even death. This leads to the need for legal relief & compensation for drug and medical device injuries.

It is important for consumers to know that they have options if they have been injured by a drug or medical device. Throughout the United States, consumers have rights under product liability laws that enable them to seek legal remedies against negligent manufacturers of pharmaceuticals and medical devices. However, the first step toward compensation for injuries suffered may involve filing a lawsuit or other legal action in a court of law.

What is the Process for Seeking Compensation?

Liability for harm caused by a manufacturer’s pharmaceutical and medical device has its roots in the laws of each state. Typically, this requires a plaintiff (the consumer) to bring a defective product claim for damages against a manufacturer for injuries sustained while using the drug or device. The normal range of damages available for these claims are:

- Recovery of Medical Expenses

- Disability

- Pain and Suffering

- Lost Earnings and Earning Capacity

- Property Damage

- Emotional Harm

Within the realm of drug and medical device litigation, there are general three types of civil claims that can be pursued against manufacturers:

Manufacturing Defect

A manufacturing defect occurs during the manufacturing process and causes the drug or device to fail to meet the design specifications established by the manufacturer itself. This defect in turn causes an injury to the consumer (or even third party). This type of claim only involves contesting the manufacturing quality of single unit of a drug or device, as opposed to the entire product line. These types of cases hold the manufacturer to a standard of “strict liability” to the injured party.

Design Defect

A design defect is a mistake in the drug or device’s intended design that caused injuries to the consumer which could have been prevented by an alternative design. Unlike manufacturing defect claims, a design defect claim examines the safety of an entire family of pharmaceuticals or medical devices.

Warning Defects

Warning Defects, also known as “Failure to Warn” or “Marketing Defects” are the result of when a drug or device manufacturer fails to provide appropriate information about a product’s known hazards and how to avoid them, and these hazards represent an undue risk of harm to consumers.

Engaging Counsel and Filing a Lawsuit

With all of this in mind, if a consumer believes that she has been injured through the negligence of a drug or device manufacturer, then the first step toward receiving compensation through our legal system is to file a lawsuit in court. Although consumers can always represent themselves in civil lawsuits, given the case management complexities involved in this type of litigation, it is generally recommended that consumers seek the assistance of counsel with expertise in this field to file their lawsuit and guide their case. Furthermore, consumers should remember that the drug and device manufacturers will undoubtedly have their own counsel representing them at all stages of your case backed by billions of dollars in insurance coverage.

A qualified attorney can also advise injured consumers about important pre-requisites to filing lawsuits. Perhaps most significantly, there are time limits on an injured party’s ability to file a lawsuit. These limits, known as “Statutes of Limitation” can preclude a potential plaintiff from their day in court if a lawsuit is not initiated within a window of time following injury. These limits vary from state to state, but are nonetheless important to any case an injured consumer might contemplate.

What Will Hiring a Lawyer Cost?

Typically in cases involving drug and device manufacturer liability, lawyers representing injured consumers (plaintiffs) will not charge an up-front fee or hourly fees. They will operate under “contingency fee agreements” which entitles them to a portion of the plaintiff’s recovery for their fees and expenses. Put simply, the attorney only gets paid if you do.

In addition to alleviating the obstacles associated with the expense of upfront retainers and hourly rates, contingency fees give consumers the added reassurance that their attorneys are just as motivated to win cases and recover the highest amount possible for their clients.

What is Multi-District Litigation?

Through your own research or encounters with legal professionals, you may have heard about “Multi-District Litigation” or MDL as it concerns cases involving drug and device manufacturers. MDL is a procedure used to consolidate and/or coordinate lawsuits which are pending before various district federal courts (in this case, manufacturing defect lawsuits). Cases are considered ideal for MDL when there are numerous cases with common questions of fact pending.

A seven-member panel of judges selected by the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, known as the “Panel on Multi-district Litigation” reviews cases for selection to MDL status, determines if they are eligible for MDL, and then selects a “transferee court” in which to host or consolidate the cases. Thereafter a single judge will oversee all of the MDL cases. If a drug and device manufacturer decides to settle a case once it has reached MDL status, plaintiffs may participate in the settlement or elect to proceed with their own case to trial.

What is a Class Action?

Similar to, but not exactly like MDL, the rules governing civil procedure in federal courts allow cases, with similar legal and factual circumstances to to be “certified” as a “class” and heard together. Some of the most famous cases to be certified as a class action lawsuit involve:

- Asbestos

- Agent Orange

- The Dalkon Shield IUD

Although class actions were popular tools for attorneys in the past, their popularity has waned in recent years for two main reasons: 1) the increasing difficulty with respect to the ability to get a case certified in district courts; and 2) the blanket settlement policy in class actions that requires all class members to accept the same settlement amount regardless of the severity of injury. For these reasons, product liability lawyers generally tend to prefer individual lawsuits that may evolve to MDL as opposed to seeking outright certification as a class.

Sources Cited (11)

1. “Products Liability: A Legal Overview”, Congressional Research Service, January 28, 2014. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20140128_R40148_73b84d8c0b03e61b9c2d64dedac6f8b44742acc5.pdf

2. Prosser, Handbook of Law of Torts, 143 (4th Ed. 1971). https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1889&context=lalrev

3. “The Road to Federal Product Liability Reform”, Victor E. Schwartz & Mark A. Behrens, 55 Md. L. Rev. 1363 (1996). https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol55/iss4/11/

4. “Enhancing Drug Effectiveness and Efficacy Through Personal Injury Litigation”, Anita Bernstein, Emory Public Law Research Paper No. 07-13; Emory Law and Economics Research Paper No. 07-12 (2007). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=990431

5. “FDA Device Regulation”, Madelyn Lauer, MD; Jordan Barker, MD; Mitchell Solano, BA; Jonathan Dubin, MD; Mo. Med. 2017 Jul-Aug; 114. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6140070/

6. “Multidistrict Litigation: New Forms of Judicial Administration”, Colvin Peterson and John T. McDermott; ABA Journal, August 1970. https://books.google.com/books?id=VRNHW_o2trgC&pg=PA737#v=onepage&q&f=false

7. “The Long Arm of Multidistrict Litigation”, Andrew Bradt, William & Mary Law Review Vol. 59 (2018). https://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3797&context=facpubs

8. “When Can Patients Sue Drug Companies?”, Robert I. Field, PhD, JD, MPH; Pharmacy and Therapeutics, May 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2697102/

9. “Is Multidistrict Litigation a Just and Efficient Consolidation Technique? Using Diet Drug Litigation as a Model to Answer This Question”, Danielle Oakley, Nevada Law Journal 2005/2006. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1370&context=nlj

10. “The Decline of Class Actions”, Robert H. Klonoff, Washington University Law Review, Volume 90, Issue 3 (2013). https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=6004&context=law_lawreview

11. “Report to Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System – An Overview of the Medical Device Industry”, MedPAC June 2017. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun17_ch7.pdf?sfvrsn=0

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Read below for some of the most commonly asked questions regarding drugs, medical devices, and the lawsuits and settlements that, at times, accompany them, when things go wrong.

I have taken a dangerous drug or undergone a procedure with a dangerous medical device. Am I eligible to file a lawsuit?

Dangerous drugs and devices include, but are not limited to, those that cause injuries due to either or some combination of a: manufacturing defect, design defect, or a defect in their marketing (“failure to warn”). If you have suffered an injury, that is – you have either taken a dangerous drug or used a dangerous medical device and experienced serious medical issues or physical harm, then you may be able to file a lawsuit to recover damages for medical expenses, pain, and suffering and possibly more. Additionally, if you have lost a family member or loved one due to death or disability because of a dangerous drug or device, you may be able to file a lawsuit as well.

Legal actions that allege harm from dangerous drugs and medical devices are typically called “product liability lawsuits”. Product liability lawsuits refer to the ability of the law to hold manufacturers or sellers liable for putting defective drugs and devices into the hands of patients and medical professionals. In essence, this is where the law works to ensure that products meet the ordinary expectations of the consumer.

Product liability lawsuits fall into three categories:

Manufacturing Defect

A product defect that occurs in the manufacturing process and which causes the product not to meet specifications set by the manufacturer itself. Manufacturing defect claims usually involve a single product unit or device (as opposed to an entire product line). Manufacturers are usually held to the standard of “strict liability” for these types of defects.

Design Defect

A design defect is a mistake in a product’s intended design that causes injuries to a consumer; and which could have been prevented by an alternate design. Unlike manufacturing defects, design defects address multiple product units across an entire line or family of products.

Marketing Defect (“Failure-to-Warn”)

Marketing or “Failure-to-Warn” defects are the result of when a drug or device manufacturer fails to provide appropriate information about a product’s known hazards and how to avoid them. If these hazards pose an undue risk of harm to consumers, the manufacturers can be held liable for that harm.

Are drug manufacturers potentially liable for the side effects caused by the products?

Most, if not all, medications have some sort of potential side effects. Sometimes side effects are less severe: insomnia; dry mouth; or drowsiness, for example. Other times, side effects can be serious and life-threatening. Either way, you – the consumer is entitled to know, in advance what the potential risks of taking any medication or using any medical device are. With that knowledge, consumers can make a judgment as to whether the risks of these side effects balance out the benefits they offer. However, if a drug or device manufacturer is aware of a side effect or defect and chooses not to disclose that side effect while the consumer is using that drug or device, the manufacturer could potentially be held liable for not sharing that information with the consumer beforehand.

When should I file a lawsuit?

There are limits on the timeframe for when injured parties can file a lawsuit alleging product liability and they vary by state. Known as “Statutes of Limitation” or “Statutes of Repose”, they require injured parties to file claims within a specified period of time either after they have been injured or the injury is discovered or when they should have known about or discovered their injury.

The time limits for filing a lawsuit can be as narrow as two years in some states to as broad as four years or more in others. It is important to know what the statute of limitation or repose is in your state before filing a lawsuit. If an injured party does not file a lawsuit before the statute expires, the Court can throw out the case despite how meritorious the claims are within.

Click here for an up-to-date list of Statutes of Limitation and Repose by state.

Who can sue for harm from dangerous drugs and devices?

If you:

- Personally, have been injured by a dangerous drug or Medicaid device

- Are the legal guardian of someone injured by a dangerous drug or medical device

- You are the representative of the estate of someone who has died from a dangerous drug or medical device;

You potentially have the “standing” to bring a lawsuit for damages if that lawsuit alleges one of the three product liability claims discussed above.

Should I hire a lawyer to file a lawsuit?

Generally speaking, the legal system and courts of the United States do not bar non-attorneys from representing themselves in lawsuits. With that in mind, lawsuits concerning serious injuries and in particular, products liability lawsuits, involve complex procedural rules, briefings, motions, arguments and rules concerning the collection and introduction of evidence. Additionally, it helps to have a skilled negotiator with you during encounters with opposing counsel for the manufacturer. And you can be assured – they will have a team of highly compensated professionals on their side. Therefore, it is generally always a good idea to hire an experienced legal professional to handle your case and advise you about your options.

Which lawyer should I choose?

Selection of a lawyer to represent your interests is a profoundly personal choice and one which should be guided principally by your level of comfort and trust in his or her abilities to effectively pursue your case and achieve a favorable outcome. With that in mind, you should, at a minimum, hire counsel with experience in product liability and who has experience litigating these types of cases before the court. Furthermore, most attorneys in the field of products liability law will always offer a free initial consultation to any potential client with whom they are meeting to discuss a case.

How much will it cost to hire a lawyer?

In the field of products liability, attorneys will almost exclusively handle cases on a “contingency” fee basis. This means that you will not be expected to pay an up-front retainer, hourly legal fees or the expenses associated with litigation. The attorney’s fees and expenses are paid as a percentage of your recovery (typically 30-40% depending upon the state where the attorney is licensed and the amount recovered) either as a result of litigation or settlement between the parties. In some cases where your lawsuit is part of a larger “class action” or “multi-district litigation”, the Court will set the rate of contingent fees.

What happens if I lose my case?

Generally speaking, if you lose your case and you have a contingency fee agreement with your lawyer, you will not be on the hook for any additional expenses or the other party’s attorneys fees. However, there are unique rules concerning these provisions in each state. Be sure to ask your attorney about them before signing an agreement for representation.

What damages can I seek for harm from a dangerous drug or device?

The level and types of damages that a consumer who has suffered harmful side effects can seek vary largely by the factual circumstances of each case. You will want to talk about these facts in great detail with your attorney. Bearing that in mind, sufferers may be entitled to: compensatory/economic damages; non-economic damages; and possibly punitive damages.

These are more commonly framed as:

- Medical Costs

- Lost Wages

- Non-Medical Expenses

- Pain and Suffering

Punitive damages are those which are awarded by the Court for harm suffered as the result of intentional (i.e. more than negligent) conduct on the part of a drug or device manufacturer. They are intended to “punish” the malfeasance of the manufacturer inasmuch as they compensate the victim.

When will I receive payment?

There is no hard and fast rule as to how quickly your case will be resolved, and no guarantee whatsoever that it will be resolved in your favor. Whether your case is filed as an individual lawsuit, class action, or MDL, depending upon when it is filed and the factual circumstances of your case, it could take weeks or even years before a harmed party receives payment.

Typically lawsuits conclude in either one of two ways:

- Judgment: The harmed party and the manufacturer present their cases in court, either before a judge or a jury and a verdict is reached. If the verdict is in favor of the harmed party, then the judge or the jury will set a damage award. The losing party may still yet appeal the case or the damage award, which could further prolong the time any amounts are paid to the harmed party.

- Settlement: The parties to a lawsuit may meet prior to heading into the courtroom and reach an agreement on an amount to be paid to the harmed party instead of going through the rigors of either a bench or jury trial. The timeframe for payment of the settlement amount will depend upon the agreement of the parties, as well as the rules of the court where the lawsuit was filed

Sources Cited

1) “Civil Statutes of Limitation” https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/statute-of-limitations-state-laws-chart-29941.html

2) “Time Limits for Filing Product Liability Cases: State-by-State” https://injury.findlaw.com/product-liability/time-limits-for-filing-product-liability-cases-state-by-state.html

3) “Time Limits for Filing a Defective Product Liability Claim” https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/time-limits-filing-product-liability-claim-29558.html

4) “What is Product Liability” https://injury.findlaw.com/product-liability/what-is-product-liability.html

5) “Multidistrict Litigation: New Forms of Judicial Administration” https://books.google.com/books?id=VRNHW_o2trgC&pg=PA737#v=onepage&q&f=false

6) “When Can Patients Sue Drug Companies?” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2697102/

7) “FDA Device Regulation” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6140070/

8) “Products Liability: Major Treatises by Topic” https://lawresearchguides.cwru.edu/majortreatises/productsliability

9) “Products Liability in the United States” file:///Users/AsherLaw/Downloads/Product%20Liability%20in%20the%20United%20States%20Issues%20for%20Dutch%20Companies.pdf

10) “Owens and Davis on Products Liability” http://umil.iii.com/record=b2012693

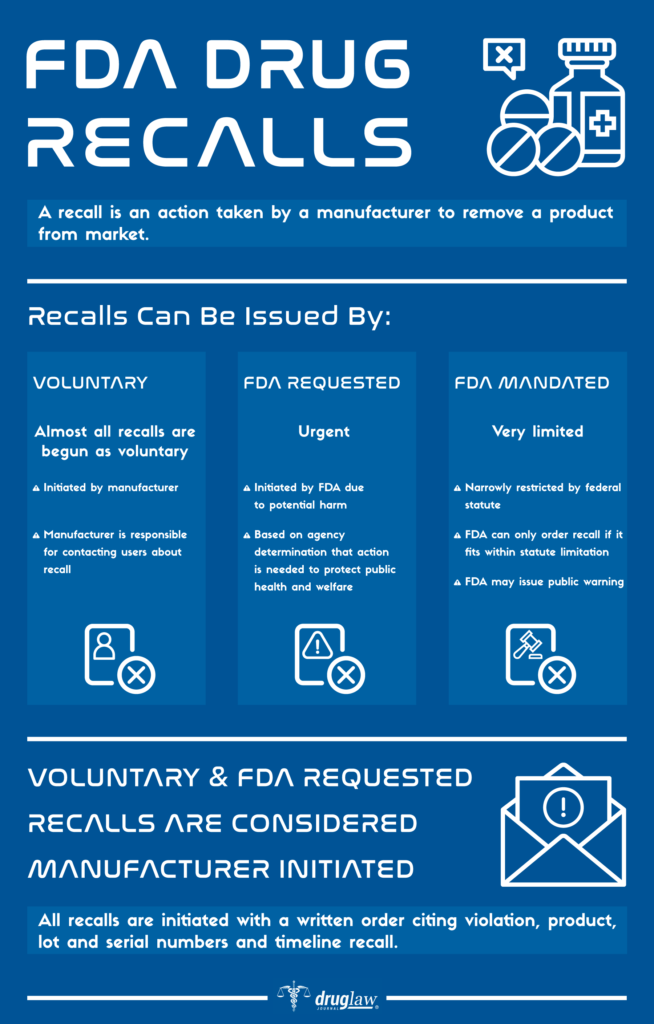

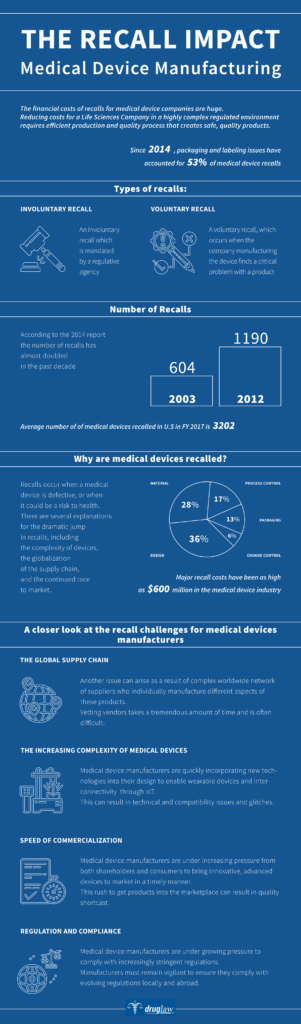

FDA Recalls – What Are They and What Do They Mean?

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is charged with ensuring that a range of consumer products, like drugs, vaccines and medical devices, are safe and effective. However, most patients and consumers probably don’t realize that for the most part, the FDA is relying upon manufacturers to conduct their own tests and studies for later review by the agency. And then once the drug or device is out on the market, the FDA further relies upon manufacturers to conduct post-market review and report any issues back to the FDA, which could then initiate the need for an FDA Recall.

Sometimes the FDA and manufacturers will conclude that an approved drug or device is, in fact, not safe for use or consumption and needs to be removed from the market. The mechanism for doing so is called a “recall” and the level and depth of the FDA’s involvement in the recall depends a great deal on communication and cooperation with manufacturers who are sometimes reluctant to pull drugs and devices which are huge profit centers for them.

What Is Involved in an FDA Recall?

Typically, if a drug or device manufacturer or the FDA itself, decides that a device or drug is not safe and therefore should not be available to patients and consumers in the marketplace, a recall will be issued. More often than not, the reasons for a recall can range from:

- The drug or device causes dangerous side effects.

- Consumers have used the drug improperly causing serious injury or death;

- The FDA has discovered a safer alternative to the drug or device.

Different types of recalls can be issued based upon the relative danger of illness or harm posed by the drug or device:

| Type of Recall | Scope |

| Class I Recall | There is a reasonable probabilty that a consumer’s use of or exposure to a drug or device will cause serious health problems or death. |

| Class II Recall | Use of or exposure to a drug or device may cause temporary or medically reversible health problems, or there is a remote risk that the drug or device will cause serious health problems. |

| Class III Recall | Use of or exposure to a drug or device is not likely to cause adverse health consequences. |

| Market Withdrawal | The drug has a minor problem that the FDA would not normally monitor. For example, the manufacturer removes a drug from the market because of after-market tampering vs. a problem with the drug itself. |

| Medical Device Safety Alert | A medical device has an unreasonable risk of causing substantial harm. |

Who Issues a Recall?

There are three routes to triggering a recall:

1) The Manufacturer

It identifies the issue internally and then initiates the recall process. This is, in fact, the most common type of recall.

2) Voluntary Recall

The FDA informs a manufacturer that its product is defective and suggests or requests that the manufacturer recall the product.

3) Mandatory Recall

If a manufacturer refuses to recall a product, the FDA has regulatory authority to either seize a product or ask the courts to force the manufacturer to recall the product.

Once a manufacturer begins the drug recall process, it must notify the FDA and then follow-up with progress reports on the success of the recall. If the FDA issues a mandatory recall order, the manufacturer will usually comply. Rarely has the FDA used its powers to seize a drug or device.

How Will I Know if a Drug or Device Has Been Recalled?

The FDA and manufacturers have several routes with which to notify consumers and patients about product recalls. Most notably:

- Direct Notification: Manufacturers affirmatively telling the wholesalers, doctors and pharmacists in its retail supply chain about the recall and what to do with the product.

- Public Notification: The FDA reports on its Class I safety recalls routinely on its web site: “Recalls, Market Withdrawals and Safety Alerts”. Typically Class II and Class III recalls can be found in the FDA’s regularly published enforcement alerts.

- Media Notice: Popular and widely used drugs and devices which are recalled will usually attract a great deal of media attention.

What Are the More Noteworthy and Recent FDA Recalls?

| Product | Recall Date | Reason |

| Zantac (ranitidine) | 2020 | Concern over contamination by NDMA, a probable human carcinogen. |

| Bextra (valdecoxib) | 2005 | Concern over increased risk of heart attack and stroke in patients. |

| Eliquis (apixaban) | 2017 | Concern over a packaging error that mis-labeled the dosage. |

| Vioxx (rofecoxib) | 2005 | Concerns over increased risk of heart attack and stroke in patients. |

| DePuy Knee | 2010 | Concerns over high failure and replacement rate as well as functionality of the design. |

Sources Cited (14)

1) “What Is a Medical Device Recall?” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/medical-device-recalls/what-medical-device-recall

2) “Recalls, Corrections and Removals (Devices)” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/postmarket-requirements-devices/recalls-corrections-and-removals-devices

3) “Drug recall: An incubus for pharmaceutical companies and most serious drug recall of history” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4286830/

4) “The World’s Biggest Medical Device Recalls” https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/features/biggest-medical-device-recalls/

5) “FDA Regulatory Procedures Manual” https://www.fda.gov/media/71814/download

6) “Industry Guidance for Recalls” https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts/industry-guidance-recalls

7) “Characteristics of FDA drug recalls: A 30-month analysis.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26843501

8) “FDA 101: Product Recalls” https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/fda-101-product-recalls

9) “FDA Drug Recalls” https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/fda-drug-recalls-32997.html

10) “Study Reveals Most Common Reasons for FDA Recalls” https://www.empr.com/uncategorized/study-reveals-most-common-reasons-for-fda-recalls/

11) “Medical Device Recalls and the FDA Approval Process” Medical Device Recalls and the FDA Approval Process

12) “Critics Assail FDA Medical Device Approval Process” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3171816/

13) “Drugs and Devices: Comparison of European and U.S. Approval Processes” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2452302X16300638

14) “The FDA’s Authority to Recall Products” https://nationalaglawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/crs/RL34167.pdf

Black Box Warnings

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has primary responsibility for regulating what must be included on the labels, including Black Box warnings, for prescription pharmaceutical medications and biological products. What is included on the label derives primarily from disclosures to the FDA by drug manufacturers and are submitted as part of the approval process. Although the FDA drug approval process imposes many requirements on manufacturers in the drug “pre-approval” stage, these companies continue to have responsibility for monitoring the ongoing safety and efficacy of their products in “post-market”.

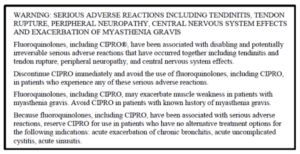

After approval, the FDA may require drug manufacturers to include additional new information on drug labels, such as boxed warnings which advise doctors and pharmacists that a particular drug may cause serious adverse reactions or other problems. These are known as “black box warnings” and are reserved for those drugs which have demonstrated a potential for side effects which can lead to death, disability or serious injury.

What Is the “Black Box” Warning?

The black box is the most substantial and serious of the on-label warnings that the FDA issues for drugs, while still allowing them to remain on the market. The name “black box” comes from the black-lined border around the text of the warning. Black box warnings must appear on the label of the prescription in order to alert physicians, pharmacists and consumers about safety concerns, serious side effects or risks to life. The information in a black box warning must provide a concise summary of the adverse effects and risks associated with the drug.

Here is an example of an FDA mandated black box warning on a label for Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics:

How Well Do Physicians and Pharmacists Understand the Warnings?

Although the black box advises consumers about serious side effects and risks, its primary purpose is to advise doctors and pharmacists as “learned intermediaries” and elevate the information to their attention. The FDA itself notes that black boxes are “…designed to make information in prescription drug labeling easier for healthcare practitioners to access, read and use to make prescribing decisions.”

Doctors are trained to be aware of the presence of black box warnings and as a general rule, always want their patients to have as much informed consent about their prescriptions as is possible. Many physicians have affirmed that black box warnings do affect their prescribing and treatment decisions – with some admitting to a hesitancy to prescribe anything with a black box warning unless no other treatment options or therapies are available.

Unfortunately, reports over the years suggest that the influence of black box warnings on physicians is not uniform owing to either a lack of understanding about the meaning of the black box or just simply being unaware of the warning itself. In a Harvard Medical School study of 930,000 ambulatory care patients, it was learned that 42% of patients had received prescriptions for black box labeled medications and that corresponding physician compliance with the recommendations on the label were “variable” in nature.

Furthermore, non-profit foundations and agencies which monitor the FDA have expressed concerns about the effectiveness of black box warnings. The sheer volume of post-market warnings issued by the FDA is leading some physicians to complain of “data fatigue” as the cause for overlooking drug warnings. For example: in 2004, the FDA issued 68 safety alerts for market recalls for drugs and devices. In 2005, that number shot up to 127. Accordingly, some experts have even gone so far as to claim that the FDA is losing its ability to influence the practice of medicine and prescribing of drugs, brandishing estimates that as many as 80% of safety warnings are overlooked by physicians and pharmacists.

The FDA “Fast Track” Process

If physicians and pharmacists are overwhelmed by warning data coming from the FDA, is it possible that too many dangerous drugs are making it through the approval process without further study? Some experts think so.

In 1988, the FDA introduced its first “fast track” drug approval process to facilitate the “development and expedite the review of drugs to treat serious illnesses and fill unmet medical need”. In essence, fast track was created to shorten the approval process for serious or rare diseases, especially those without other available treatments. However, in 1992 fast track was augmented by the FDA with two additional avenues for approval: “priority review” and “accelerated approval”.

Since 1992 and the enactment of these additional expedited aveues, median approval times for new drugs decreased from 33.6 months to 16.1 months. Accordingly, some experts and their counterparts in the drug manufacturing industry point to this fact and argue that the fast track process provides benefits for society-at-large with more medications getting onto the market in shorter time. However, others argue that it has also undermined safety fundamentally. They note that between 1999 and 2009, outpatient prescribers in the United States wrote more than 30 million prescriptions for each of nine drugs (for a total of 270 million prescriptions) that were subsequently removed from the market for safety reasons or which received black box warnings for potentially lethal side effects.

One statistical study, researched over several years and presented for review in 2014, concluded that newly approved drugs have a one-in-three chance of acquiring a new black box warning or being withdrawn for safety reasons within 25 years of FDA approval. This study made the recommendation that the FDA: a) strengthen drug approval standards (i.e. increase approval times); and b) that physicians should rely on drugs with longer market exposure and established track records – unless it involves a truly breakthrough therapy.

Future of Black Box Warnings

For too many physicians, the black box warnings are opaque in their meaning and lack the reasoning that seasoned medical professionals utilize when evaluating the needs of their patients. Furthermore, the FDA relies upon a system of post market “surveillance” for learning about adverse effects, that is itself wholly reliant upon the drug manufacturer collecting and reporting adverse data to the FDA. For these reasons, many both in the consumer safety and drug regulatory fields feel that the FDA should: a) improve and strengthen the methods it uses to communicate adverse side effects to physicians and pharmacists; b) increase scrutiny and approval times for drugs in the pipeline; and c) enhance post-market surveillance with less reliance on reporting by the manufacturers themselves.

Sources Cited (14)

1) “A Guide to Drug Safety Terms at FDA” https://www.fda.gov/media/74382/download

2) “What Does it Mean if My Medication Has a ‘Black Box’ Warning?” https://health.clevelandclinic.org/what-does-it-mean-if-my-medication-has-a-black-box-warning/

3) “New and Incremental FDA Black Box Warnings From 2008 to 2015” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29215916/

4) “Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Formulary Restrictions After Postmarket FDA Black Box Warnings” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31663461/

5) “The meaning behind black box and other drug warnings” https://www.healio.com/pediatrics/practice-management/news/print/infectious-diseases-in-children/%7B2f3d205a-694f-4ff0-9d60-56563e17f149%7D/the-meaning-behind-black-box-and-other-drug-warnings

6) “Black box” 101: How the Food and Drug Administration evaluates, communicates, and manages drug benefit/risk” https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(05)02325-0/fulltext

7) “Expedited drug review process: Fast, but flawed” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4936080/

8) “Era Of Faster FDA Drug Approval Has Also Seen Increased Black-Box Warnings And Market Withdrawals” https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0122

9) “Why You Should Pay Attention to Black Box Warnings on Medication” https://www.verywellhealth.com/black-box-warnings-1124107#what-does-one-look-like

10) “Physicians May Overlook Black Box Warnings” https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/pn.41.6.0013

11) “Consumers Tune Out FDA Warnings” https://money.cnn.com/2008/02/22/news/companies/fdawarning_fatigue/index.htm

12) “The consent risks with ‘black box’ warning medication” https://www.hrmronline.com/article/the-consent-risks-with-black-box-warning-medication

13) “What is a Black Box Warning for a Drug?” https://www.everydayhealth.com/fda/what-black-box-warning-drug/

14) “Doctors often ignore ‘black box’ warnings on drugs” https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/120625-doctors-often-ignore-black-box-warnings-on-drugs

510(k) Device Clearance

According to the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA), all medical device manufacturers must register their facilities and list their devices with the Food and Drug Administration. In the U.S., these devices must generally follow one of two paths to market, either: the Pre-Market Approval (PMA) application process; or the 510(k) Device Clearance “notification” which allows device manufacturers to bypass the more rigorous PMA process entirely. The FFDCA does not require that every medical device on the market in the U.S. be subjected to FDA review. However, those devices which present moderate-to-high risk issues for the health and safety of patients and consumers must be subjected to a review process prior to entry in the market.

Bearing this divergence in mind, the FDA set a new record for device approvals across the board in 2018, with most coming through the 510(k) clearance process. Furthermore, between 1996 and 2009, the FDA approved 48,402 applications through 510(k) clearance and generally speaking, roughly 85% of these applications are cleared annually on the basis that the applicant is “substantially equivalent to an earlier, approved device.

In the meantime, between 2005 and 2009, there were 113 device recalls on the basis of issues that the FDA determined could cause serious health problems or death. Over 71% of these devices were cleared through the 510(k) process. This surge in recalls has prompted many advocates for patient safety to question a system which they feel is allowing too many dangerous devices through which cause harm or worse to the patients they are supposed to help.

Overview of the 510(k) Clearance Process

The FDA regulates virtually every medical device on the market in the U.S. today. The amount and depth of scrutiny, regulatory controls and in some instances, restrictions on marketability, are all tied to the FDA’s medical device classification system. Those device classes are:

| Classification | Threshhold | Examples |

| Class I | General controls are sufficient to provide reasonable asurance of the safety and effectiveness of the device. The device has a low risk of illness or injury to patients. | Elastic bandages, examination gloves, handheld surgical instruments. |

| Class II | General controls are insufficient to provide reasonable asurance of safety and effectiveness of the device. These devices pose a moderate risk to patients. | Powered wheelchairs, infusion pumps, surgical drapes. |

| Class III | Cannot be classified as either Class I or Class II because there is insufficient information that special controls would provide reasonable assurance of the device’s safety and effectiveness. These devices are generally purported to be for use in supporting or sustaining human life or for a use which is of substantial importance in preventing impairment of human health. | Heart valves, silicone gel-filled breast implants, implanted cerebella stimulators; metal-on-metal hip joints and certain dental implants. |

Medical devices which fall under Class II and Class III which are not “substantially equivalent” to an already approved medical device must route through the FDA’s rigorous PMA process. That means the device manufacturer will have to submit clinical data to support claims about the safety and effectiveness of the device.

Devices which can claim substantial equivalence to an already approved device may divert through the abbreviated 510(k) process as an alternative to PMA. Instead of demanding evidence for approval, as with the PMA process, the FDA instead “clears” a device for the market as long as the manfucatrer can demonstrate its equivalence to an already approved device. In other words, within 510(k), the FDA is not actually examining any device to determine if the manufacturer’s claims about its safety or effectiveness are actually true. Note: about 80% of all medical devices submitted to the FDA are routed through 510(k) clearance.

510(k) Clearance and Potential Dangers from Lack of Oversight

Medical journals and public interest research groups for years have noted that “fast-tracking” devices to the market, such as through the 510(k) clearance process potentially correlates to a spike in device recalls. One of the most prominent product recalls for a device claiming substantial equivalency involved a common device implanted in thousands of patients. In 2005, the DePuy Orthopaedics division of Johnson and Johnson marketed a new metal-on-metal replacement hip-joint design. The new joint design was cleared through the 510(k) clearance proces and was implanted in over 100,000 people. However, after receiving a barrage of complaints of pain and illness stemming from erosion of the metallic parts, the DePuy hip was recalled in 2010.

Additionally, in 2018, as part of a long-running collaborative investigation between the AP, NBC and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, it was learned that across all types of medical devices, more than 1.7 million injuries and 83,000 deaths were reported to the FDA over the previous decade. Between 2008 and 2017, it was found that nearly one quarter of all device injury reports came only from a few devices which went through the truncated approval process:

- Surgical Mesh – 60,795 injuries

- Hip Prosthesis – 103,104 injuries

- Spinal Stimulator – 78,172

- Defibrilator – 59,457

- Insulin Pump Implant – 60,561

- Insulin Pump with Sensor – 94,826

Despite these issues, the FDA does not believe that its role as a regulator has been compromised or rendered less effective than perhaps is believed. Although the agency has expressed some reservations about the limitations of the data it collects and its ability to assess death or injury due to the use of any medical device, it does not believe its oversight role is failing. At a recent industry conference, Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, the Director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, stated that “There are over 190,000 different devices on the U.S. market. [The FDA] approves or clears about a dozen new or modified devices every single business day… The few devices that get any attention at any time in the press is fewer than the devices we may put on the market in a single business day. That to me doesn’t say that the system is failing. It’s remarkable that the system is working as it does.” He went on to say “Unfortunately, the FDA cannot always know the full extent of the benefits and risks of a device before it reaches the market…”

The Future of the 510(k) Process